In the mid-1980s, there was a small, but established, Balkan music scene on the East Coast. Groups like Novo Selo in Philadelphia, Ženska Pesna in New York and Evo Nas in Boston had been learning, playing and singing Balkan music in traditional styles and using traditional instruments since the mid-1970s and before. The establishment of a Balkan Music & Dance Workshop on the East Coast in 1983 (see Kef Times, Fall/Winter 2001-2002) injected further energy as well as synergy, as Balkan music enthusiasts from all over the Northeast (and beyond!) got to meet each other, share musical skills and interests, and be exposed to teachers that EEFC brought from elsewhere (e.g., Stewart Mennin and his jumpstarting of Balkan brass band music, leading to the formation of Zlatne Uste in New York City and BAMCO in the Washington, D.C., area).

However, starting up a new camp on the East Coast came with additional costs, putting financial strains on the organization. (This was one of the reasons that, in the first year orientation session, campers were told that meat would be offered on the menu “at least two or three times,” triggering the East Coast flare-up of “The Great Meat Rebellion” (see Kef Times, Fall/Winter 2002-2003.)

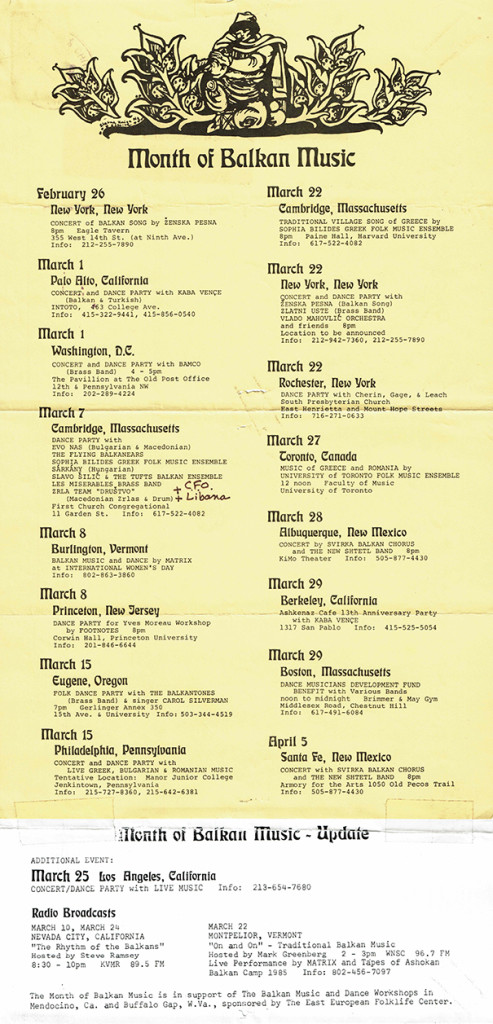

Fig. 1. Month of Balkan Music, 1986.

In late 1985 and early 1986, EEFC campers and others around the country received a request to put on local Balkan music events during March 1986 as part of a nationwide “Month of Balkan Music” celebration, sponsored by EEFC. This drive was intended to create a wider awareness of Balkan music and the opportunities to learn more about it at the camps, which would in turn hopefully increase attendance rates and income. There was a nationwide response (Fig. 1).

In Boston, area musicians who had attended the camps, plus others from around the region, joined together to produce a marathon Balkan music event. The Boston group Evo Nas, whose members had the most experience with EEFC and the camps, spearheaded the organizing, but members of some of the other bands also participated in coordinating the event, as did other folks who liked the music and wanted to help out. This gathering was the first joint appearance of many Boston-area groups who played traditional Balkan music but had come to it from so many different sources: the “folk dancer” world, the academic music and ethnomusicological world, the early music world, the feminist/women’s music world, and those who had come from their own ethnic heritage. (We also had music from “another” world—“Zurla Team Drushtovo”! [sic]) We had no idea how it would turn out!

In the auditorium of a church in Harvard Square, Cambridge, Mass., we started off the evening with a sit-down concert instead of a dance party. This was because some of the groups did not perform dance music, and also because we felt that we could attract a larger potential new audience that way. Following the concert, we had an intermission during which we stowed away all the folding chairs, and continued with a dance party to live Balkan music that extended into the wee hours of the night—another Balkan music first for Boston.

The event was a big success, with 200 people showing up, and it was so much fun that we resolved to do it again. The following year, in the same location, in the midst of a snowstorm, we had a huge crowd—a lot of people could not be admitted because we had already filled every square inch of the hall. It was stressful at the time, but it showed us that there was clearly an audience for the event!

Fig. 2. Balkan Music Night 1988 at Masonic Hall; Evo Nas is playing.

For year three (1988), we moved to a larger hall (The Masonic Hall in North Cambridge, replete with American flags, Fig. 2) and began selling advance tickets, so that we and prospective attendees would know when we had exhausted our capacity. We used that location for only two years because, during the second year’s event, the building’s neighbors called the police, reporting that it sounded like there was “a marching band playing in the hall at 2:30 a.m.!” (that would have been Zlatne Uste, Fig. 3). So we were forced to move again. That year was also when we sought sponsorship from the Folk Arts Center of New England, so that we would have nonprofit status. However, the event maintained its own independent organization and finances and has been self-supporting since the very start.

Fig. 3. Balkan Music Night 1989; Zlatne Uste is playing.

Fig. 4. Balkan Music Night in Concord, Mass.

After a single year at another location—only an interim solution because we were required to end by midnight (!)—we moved to our current location in historic Concord, Mass., about 15 miles west of Boston and Cambridge, to a historic town armory (built 1887) that has been transformed into 51 Walden Performing Arts Center, which offers a large main hall with a sprung wooden floor (Fig. 4) for dancing, and concert seating for approximately 400 people.

The building has a second venue: a smaller dance studio on the second floor. We named that second room the “Kef-ana” because we were not allowed to bring food or drinks up there, so it has always had “kefi, not kafe.” At first, we used it only for jamming and other informal (and even non-Balkan) sets; more recently, we have used it as a formal second venue, scheduling groups up there as well as in the main hall, essentially doubling the number of groups that can perform. The building’s lobby offers space for generous offerings of complimentary refreshments and hot and cold drinks, and attendees can browse the CD, sheet music and other offerings of “The Little Shop of Horas®,” operated by the Folk Arts Center.

Over the past 31 years, we have presented performances by a multitude of Balkan music luminaries, including local and regional performers as well as special guests from across North America and from the Balkans. A complete list of performers is on the Retrospective page on our website.

In addition to the concert and dance sets, Boston’s Balkan Music Night has had a number of other signature features. In keeping with the original goal of increasing awareness of (and participation in) Balkan music, we have included a number audience participation events during the evening, generally during the breaks between the formal music sets. We always have Horo na Pesen (“dance to singing”), when we distribute song lyrics and audience singing provides the music for the dance. These have included many village songs collected in Bulgaria by Martha Forsyth, as well the a cappella Ličko Kolo and more modern songs with instrumental accompaniment. The Ladarke Sing-Along has also been a long-term feature (years before it became an institution at East Coast camp!). In addition to these singing events, we have had many instrumental “extravaganzas,” where we encourage anyone who plays (or used to play) a particular instrument to bring it and play along to a simple tune. The very first was the tambura extravaganza in 1987, when we persuaded the many Boston-area people who had obtained Macedonian tamburas in the 1970s to get them out of the closet and play along (or just drone along) to Neda Voda Nalivala. We had over 20 players show up and, although tuning beforehand probably took longer than the actual piece, it was a big success! Since then we have also had the recurring tapan extravaganza to accompany the tapan-only dance Kopačkata from Dramče, Macedonia, as well as group efforts on gajda, bitov instruments, brass, frame drum and more.

Fig. 5. Valle Tona (Albanian dance group).

We have also made efforts to include our local ethnic communities in the event. We have had the pleasure of presenting music sets by groups from the local Greek, Bosnian, Macedonian, Serbian and Turkish communities, and we have presented short performances by local community dance groups (including Albanian (Fig. 5), Bosnian, Bulgarian, Greek and Serbian) on the dance floor during the music group transitions on stage. In recent years, we have also presented Mladost, our local young people’s dance group that was formed as a group of second-generation folk dancers, directed by Andrea Taylor Blenis, herself the daughter of Conny and Marianne Taylor, who were leaders in establishing folk dancing in the Boston area.

We maintained the original format for the evening (a sit-down concert, followed by the “moving of the chairs” ritual, and a dance party into the wee hours) through 2015. Responding to perceived changes in audience preferences, the format shifted in 2016 to “all dancing, all the time” in the main hall, and “all listening” in the Kefana. We often discuss finding a new, more accessible location closer to Boston, but finding a site that is big enough, offers multiple venues, is accessible enough, allows an event to run late, offers sufficient parking, and is affordable—is a tall order!

This year’s event will take place in Concord, Mass., on March 18, 2017, from 7 p.m. to 1 a.m. Lots of information about the event, including our exciting performer lineup, and links to videos of past events, can be found on our website. We hope to see many of you there!

Henry Goldberg plays and sings in several Balkan music groups and organizes Balkan music events in the Boston area. He attended his first EEFC workshop in 1978 and has been involved in putting on Boston’s Balkan Music Night since its inception in 1986. Little known fun fact: he created the paper-cut bags that covered the bare light bulbs in the Mendocino dance hall for a number of years into the 1980s. (Henry’s cut-outs but not Henry are featured in this photo.)

Balkan music groups and organizes Balkan music events in the Boston area. He attended his first EEFC workshop in 1978 and has been involved in putting on Boston’s Balkan Music Night since its inception in 1986. Little known fun fact: he created the paper-cut bags that covered the bare light bulbs in the Mendocino dance hall for a number of years into the 1980s. (Henry’s cut-outs but not Henry are featured in this photo.)

You know when it’s January? And you haven’t seen the sun since September? And the long, grey spring stretches out ahead of you with that little twinkle called Balkan camp at the end of the tunnel? And everybody else is partying out at Golden Fest? Every year at that time we would think, we really need to have something like Golden Fest that we can go to! In our town!

You know when it’s January? And you haven’t seen the sun since September? And the long, grey spring stretches out ahead of you with that little twinkle called Balkan camp at the end of the tunnel? And everybody else is partying out at Golden Fest? Every year at that time we would think, we really need to have something like Golden Fest that we can go to! In our town! We got the hall, arranged for the Seattle Junior Tamburitzans to run the kitchen and bar, crossed our fingers and did it. We remember when we opened the doors at the first Balkan Night—the hall was full from the 4 p.m. start time; it was like stepping on a conveyer belt that was running a little bit too fast, but in a great way. Everyone was so thrilled and excited by what was happening, and we are just trying to keep that feeling continuing.

We got the hall, arranged for the Seattle Junior Tamburitzans to run the kitchen and bar, crossed our fingers and did it. We remember when we opened the doors at the first Balkan Night—the hall was full from the 4 p.m. start time; it was like stepping on a conveyer belt that was running a little bit too fast, but in a great way. Everyone was so thrilled and excited by what was happening, and we are just trying to keep that feeling continuing. BNNW was held at the Russian Center in 2012 and 2013. In 2014, it moved to St. Demetrios Hall and we expect to keep it there. Dates have ranged from as early as February 21 (scheduled for 2015) to as late as March 16. Why the roaming dates? We are trying to keep it on the weekend of Apokries (Orthodox Mardi Gras). That way, all the

BNNW was held at the Russian Center in 2012 and 2013. In 2014, it moved to St. Demetrios Hall and we expect to keep it there. Dates have ranged from as early as February 21 (scheduled for 2015) to as late as March 16. Why the roaming dates? We are trying to keep it on the weekend of Apokries (Orthodox Mardi Gras). That way, all the  Another part of our motivation is to inspire and support young people to play Balkan music, so we take whatever proceeds we make to fund scholarships to the Mendocino Balkan Music & Dance Workshop and balkanalia!. It takes a lot of work and support from community members to pull this off, and thankfully, people have been willing to work hard and help by volunteering at the festival. So far we have been able to fund three full scholarships to the Mendocino Balkan Music & Dance Workshop, and seven scholarships to balkanalia!.

Another part of our motivation is to inspire and support young people to play Balkan music, so we take whatever proceeds we make to fund scholarships to the Mendocino Balkan Music & Dance Workshop and balkanalia!. It takes a lot of work and support from community members to pull this off, and thankfully, people have been willing to work hard and help by volunteering at the festival. So far we have been able to fund three full scholarships to the Mendocino Balkan Music & Dance Workshop, and seven scholarships to balkanalia!. Each year we bring in a featured band from a specific region, and present a separate event the following night that just focuses on that band. This year we brought Kalin Kirilov and his group, and on the night after Balkan Night, the local Bulgarians put together an amazing evening of games and rituals that was delightful and meaningful. The year before, we brought Merita Halili and Raif Hyseni, and they sold out the Triple Door, full of Albanians from all over Albania—it was just electrifying!

Each year we bring in a featured band from a specific region, and present a separate event the following night that just focuses on that band. This year we brought Kalin Kirilov and his group, and on the night after Balkan Night, the local Bulgarians put together an amazing evening of games and rituals that was delightful and meaningful. The year before, we brought Merita Halili and Raif Hyseni, and they sold out the Triple Door, full of Albanians from all over Albania—it was just electrifying!

Musician, singer and teacher John Morovich specializes in the folklore of Croatia. He is artistic director of the Seattle Junior Tamburitzans, and Ženska Klapa Ružmarin. He performs regularly with the Sinovi Tamburitzans, a group he co-founded in 1979. He has created dozens of choreographies, scores for tamburitza orchestra and choirs, and has taught regularly at EEFC camps since 1987.

Musician, singer and teacher John Morovich specializes in the folklore of Croatia. He is artistic director of the Seattle Junior Tamburitzans, and Ženska Klapa Ružmarin. He performs regularly with the Sinovi Tamburitzans, a group he co-founded in 1979. He has created dozens of choreographies, scores for tamburitza orchestra and choirs, and has taught regularly at EEFC camps since 1987.