Marlis Kraft-Zemel

In 1983, Swiss-born musician Marlis Kraft-Zemel and her two sisters were touring in the U.S. with an international folk music group and wondering if they would get beyond the waiting list for the first-ever East Coast Balkan Music and Dance Workshop. When two spots opened up two days before camp started, Marlis and her sister Cornelia grabbed them. The camp experience was life-changing for both. Marlis, who now lives in the States, has returned to camp every year since and has run the children’s program since the early 1990s.

Marlis was born in Basel and grew up in Winterthur, in northern Switzerland, the second of five children. Her parents came from varied backgrounds; the kids spoke German with their dad and English with their mom. (The parents spoke French when the children were not supposed to understand it.) The kids quickly grew to be trilingual.

There were always people in and out of the house, visiting from other places, and there was always singing in the family. Marlis started playing guitar at age 10. She and her two sisters sometimes went folk dancing and Marlis was intrigued by the beautiful songs they danced to.

“I remember the day when I went into a record store in Zurich and went into the international folk music section,” she says. “I was probably 17 or 18. Somehow I put my hands on a Pennywhistlers record and they put it on for me” (in those days a record store would open a record and allow you to listen to it before buying) “and I was totally mesmerized.” Later, she would meet Ethel Raim, director of the Pennywhistlers, at Balkan camp.

Marlis attended a teacher training college in Zurich and earned an undergraduate degree in primary education, with a minor in guitar. Then she made the decision to pursue a program at Lesley College in Cambridge, Mass., called Expressive Therapies, which combined music, drama and art in what was considered a “very edgy program.”

While in graduate school, she was accepted into the Balkan music group Evo Nas (with Henry Goldberg and David Bilides, among others). After returning to Switzerland, she and her sisters started singing together more regularly, including Balkan music. One of her sisters had been to Israel and done international folk dancing there. They named their group Šarena Duga, which means “colorful rainbow” in Croatian. A few years later, some of their American cousins invited them to perform a three-week concert tour in the States. And that’s what they were doing on that fateful day when Marlis learned she could attend the workshop.

Forming Lifelong Connections

Iroquois Springs

“No sleep and boundless energy,” she says, describing the early Balkan camps. “So much fun. We were fed by dancing, the music and the camaraderie. It was magical.”

At the first camp, held at Ashokan in the Catskill Mountains, Marlis met Alan Zemel and his son, Mark. Alan was Marlis’ tambura teacher. (See Kef Times, Spring 2011, for a profile on Alan.) Alan and Marlis would eventually marry and have a daughter, Miriam; they divorced in 2006.

“My sister and I had to come back the next year,” Marlis says. “We both made lifelong connections at that camp.” Marlis’ sister Cornelia connected with Souren Baronian, on staff teaching doumbek, and they later formed the group Transition with Haig Manoukian.

“I was absolutely intrigued to meet Yianni Roussos with his hand-crafted santouri,” says Marlis, who had heard a santouri player in Greece. Roussos, who would later become a frequent member of the teaching staff, wasn’t teaching that year but was there to support the Greek musicians. “I had been trying to play some Greek tunes on my Swiss hammered dulcimer but it didn’t quite work.” Thus began a lifelong love of santouri; Marlis regularly played with Roussos for a couple of years at a Philadelphia restaurant and still sits in sometimes.

Children’s Program at the Workshops

In the early years, bringing children to Balkan camp was controversial. Those who did bring kids had to arrange for childcare, and there was no children’s programming. See “Kids at Camp” from the Fall 2007 Kef Times.

Alan’s son, Mark, was the first and only kid at that first camp, and Marlis and Alan were proponents of bringing kids to camp; many community members were adamantly against the idea, Marlis says. But gradually more and more people had kids they wanted to bring and expose to the scene, and about 20 years ago Marlis offered the first children’s program. Shortly thereafter it became a regular part of the program and an official staff position. Eventually she applied for an assistant, which is now a continuing work-exchange position.

Marlis was a natural for this work. Besides her educational background in primary education, her day job for many years was teaching music at Oak Lane Day School in Philadelphia; she was also program director for Oak Lane’s summer camp. Over the years she has also worked with children on oral history and drama productions at KlezKamps. These days she teaches part-time at the Community Partnership School and offers private lessons to adults and children on guitar (classical and folk), recorder and ukulele.

She is keen on exposing children to different kinds of music, rhythms and scales. At Balkan camp, where her students range widely in age and interest, she generally includes singing, storytelling, oral history, instrumental music, dancing, drama and/or puppetry, and crafts. Plus treasure hunts, hooping and trips to the pond. As much as possible she involves other program staff to work with the kids, to teach a dance or demonstrate an instrument. She likes to change the focus each year: one year on a particular country, another year on a dramatic production of a Balkan story.

“Last year, because it was the 30th year [of the East Coast workshop], every day we interviewed one of the old-time members of the staff, for the kids to find out what Balkan camp was like earlier, and also for them to learn how to interview,” she says. “The children interviewed teachers, including Steve Kotansky, Carol Silverman and Jerry Kisslinger, and also David [Bergman] and Bob [Nowak] from the kitchen. Every day we had a surprise guest. It was really fun.”

Marlis’ longtime wish to expand the opportunities for children and teens at the East Coast camp came true when EEFC asked Sarah Ferholt, a music teacher and member of Zlatne Uste and Veveritse Brass Bands to start the official youth band, Čoček Nation.

Current Projects

Marlis is excited about a teacher’s training week she will attend this spring offered by Al-Bustan Seeds of Culture, an organization dedicated to presenting and teaching Arab culture through the arts and language. The program includes singing, percussion, instrumental music and cultural talks.

“It’s very intense and full, with top-quality people,” she says, citing the influence of Arabic culture on the Balkans via the Ottoman Empire. “I will probably take some of what I learn for the children’s program at Balkan camp this year.”

“A place where you can be the person you are at the center”

“Balkan camp has now been a part of my life longer than the years without,” Marlis says. “I have been to every single [East Coast] camp, and it has deeply influenced my life and my teaching. The incredible variety of people there, the crazy moments at camp—suddenly all of ZU is naked in the pool. Or Esma pulling the whole group like a magnet. Silly moments, people playing pranks, staying up to the wee hours, talking about God knows what, playing and singing.

“Balkan camp is a place where you can be the person you are at the center—the kid in ourselves,” she continues. “In the professional world we often have to put on a certain role. At Balkan camp the façade falls and we are who we are. Also it’s an opportunity for kids to see that grownups can be silly; some kids don’t get to see that.”

That thought echoes a 2009 EEFC fundraising letter, in which Marlis’ daughter Miriam, then a senior in high school, wrote: “. . . for one week I'm given the chance to see my parents as people, real people. I'm knee-deep in the time of my life where all I want to do is break away from my parents’ restrictions and their forced guidance. For one week I view my father as the musician and social butterfly I know he is. For one week I view my mom as the kids’ music teaching genius she is . . . Balkan camp offers a week to reconnect with the music and the EEFC community, but most of all, your family.”

Moreover, the Balkan camp community is “incredibly supportive,” carrying families through tough times and sharing each other’s life celebrations, Marlis adds.

“I think my longevity with EEFC has really aided the program,” Marlis says. “Because I know so many of the staff that they will happily come and share their talents. And with kids, a certain continuity is very helpful. When I finally pass along the baton, I know somebody else will do their own thing, and that’s fine, but I hope the transition will be gradual. I think this is a really, really important program for retaining young families and for the future of Balkan camp."

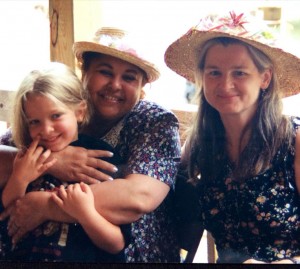

Photos: Margaret Loomis.