Expanding Our Range

Julie Lancaster (photo by Rick Cummings)

Now that Kef Times is planned for publication three times per year (May, September and December), we’re delighted to be able to expand the range of subjects addressed and authors featured from our community.

Our cover story is a profile on Mark Forry, a longtime EEFC workshop faculty member whom I’ve long wanted to interview. Next up is Laura Shannon’s in-depth article about a ancient Twelfth Night tradition that is alive and well in northern Greece.

In this issue we debut four (really? four? what were we thinking?) new sections. The first is In the Hood—about how people have created EEFC-inspired music scenes or events in their own home towns. This installment is by Ruth Hunter and John Morovich, about Balkan Night Northwest in Seattle.

Other new sections are Balkan Songs, edited by Bill Cope; this issue’s song transcription and translation were a collaboration between Bill, Miamon Miller and Sophia Bilides; Eastern European Threads (costumes and textiles) edited by Wendi Kiss; and Gems from the EEFC Listserv (or Gems from the Listserv Archive, depending on just how old the gems in question are).

I hope you’ll find these new sections so inspiring that you pass the articles along to friends to read, and maybe even decide you’d like to contribute something for an upcoming Kef Times. If you do, just shoot me an email with your ideas.

As in every issue, you will also find the New & Notable section about new releases in our community, and workshop photos from the latest camps. (Note: the 2014 Kef/Crum and other scholarship recipients will be featured in the next issue.)

We’d love to hear from you! Just send me an email if you have comments or ideas.

Gems from the Listserv

In this section we bring you some recent posts from the EEFC’s listserv—one entertaining and two practical.

The listserv is a discussion list where subscribers post and discuss items of interest. It has a searchable archive going back to 1993 (available to anyone) and has been overseen by list angels Noel Kropf and Emerson Hawley for most of that time. (Click here for the archive search page.)

Topics range from finding lyrics to sharing music and dance videos, publicizing events in your local area, scholarly discussion on ethnomusicology topics, travel tips, practical matters such as gajda maintenance, and much more.

Not everyone in our community subscribes to the listserv, and until now there hasn’t been an easy way to share the wealth to be found there with non-subscribers both within and outside our community.

In future issues, we plan to include some older treasures from the archive. But we need your help. If you can think of a memorable listserv discussion you enjoyed that might be of interest to Kef Times readers, please drop us a note referencing the archived post.

Or . . . volunteer to go through a year’s worth of archived posts and see what you turn up of interest from that year—say, 1997. Or 2001. Your choice. (Let us know so we don’t have multiple people spending time digging through the same year.)

As a child, I grew up in a Russian Orthodox parish [in the U.S.] where many of the parishioners were deformed by WW I, the Stalin terror or WW II . . . eyes, parts of faces, missing body parts, that sort of thing. In many cases combined with the attendant psychiatry as well . . .

As a child, I grew up in a Russian Orthodox parish [in the U.S.] where many of the parishioners were deformed by WW I, the Stalin terror or WW II . . . eyes, parts of faces, missing body parts, that sort of thing. In many cases combined with the attendant psychiatry as well . . .

When I first became aware that the Americans had come up with decaffeinated coffee, this news came to me via the parish in the form that it was roundly judged to be “a communist plot to weaken America.”

It took me a few years to drill down to the reason for this view:

Coffee was considered to be the devil's drink . . . barbarian . . . nothing like Russian tea. Pilgrims were occasionally scandalized, in going to Greek monasteries, to be offered this brew. However, during the WW I disaster, Russian troops frequently found themselves without medicine. The nurses and doctors quickly discovered that really strong coffee could keep some of the wounded from going into shock and dying. Hence, among the first two or three waves of the Russian emigration, coffee was considered a somewhat beneficial medicinal drink to strengthen the constitution, even though it had a dodgy foreign past.

This post appeared on the EEFC listserv on Mon, September 1, 2014, and is reprinted here with permission from the author. Alexander Eppler, a multi-instrumentalist who has taught kaval at the EEFC Balkan Music & Dance Workshops, is a flute maker in Seattle.

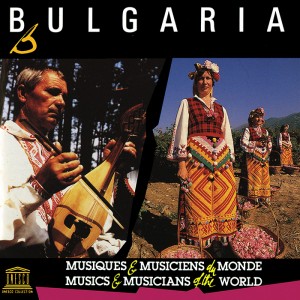

UNESCO Collection’s 1983 “Bulgaria” recording is available for download or as a compact disc.

Just thought I'd pass along this notice I got from Smithsonian Folkways in Washington, DC. . . . and you can download the liner notes . . . hurray!

The Smithsonian Folkways reissue of two albums per week from the UNESCO Collection of Traditional Music continues! Read the latest guest blog posts, and check back weekly to explore musical traditions from around the world. Click here to find out more.

On September 19, Larry added the following comment for Kef Times:

The recordings were made in 1983 with the cooperation of both Balkanton and Bulgarian National Radio and most tunes were probably not released previously. The original liner notes (in English and French) are included as a PDF with the CD, or they can be downloaded here.

You can also use Smithsonian Folkways’ search engine to find other music of interest.

This post appeared on the EEFC listserv on Thursday, Sept. 11, 2014, and is reprinted here with permission from the author. Larry Weiner is a dance teacher and tapan player in Washington D.C. You can read an interview with him in the Fall/Winter 2001-02 Kef Times.

[In response to a post from Dean Brown, who recently tracked down a particular Romani tune taught by Carol Silverman at an EEFC workshop by finding the entire 1982 Jugoton album on YouTube.]

[In response to a post from Dean Brown, who recently tracked down a particular Romani tune taught by Carol Silverman at an EEFC workshop by finding the entire 1982 Jugoton album on YouTube.]

Rachel writes:

When I’m looking for song credits I have had great luck using the site discogs.com. You can find the Jugoton Trajko Ajdarević Tahir LP listed and pictured there. (Title: Romske Pjesme: Ajde amenca, e bahtale Romenca). Mustafa Ismailović is indeed listed as the composer of “Na kelav, na gilavav.” Unfortunately the album is minimally cataloged here, but you can read the verso of the album cover from the photo and find the track credits.

The cool thing about Discogs is that you can sign on to enter albums yourself. If you’ve got the time and energy to do this kind of cataloging so many people can benefit! I bought the above record myself years ago at the Zagreb Jugoton store. Maybe someday I’ll pull it out from storage and compose a better Discogs entry.

Rachel M.

P.S. I also like being able to pull album cover images from the Discogs entries to use for my iTunes collection.

This post appeared on the EEFC listserv on Thursday, Sept. 11, 2014, as part of a conversation started by Dean Brown and is reprinted here with permission from the author. Rachel MacFarlane is the EEFC’s Workshop Manager and production manager of Kef Times.

Cool Resource: Discogs

[In response to a post from Dean Brown, who recently tracked down a particular Romani tune taught by Carol Silverman at an EEFC workshop by finding the entire 1982 Jugoton album on YouTube.]

[In response to a post from Dean Brown, who recently tracked down a particular Romani tune taught by Carol Silverman at an EEFC workshop by finding the entire 1982 Jugoton album on YouTube.]

Rachel writes:

When I’m looking for song credits I have had great luck using the site discogs.com. You can find the Jugoton Trajko Ajdarević Tahir LP listed and pictured there. (Title: Romske Pjesme: Ajde amenca, e bahtale Romenca). Mustafa Ismailović is indeed listed as the composer of “Na kelav, na gilavav.” Unfortunately the album is minimally cataloged here, but you can read the verso of the album cover from the photo and find the track credits.

The cool thing about Discogs is that you can sign on to enter albums yourself. If you’ve got the time and energy to do this kind of cataloging so many people can benefit! I bought the above record myself years ago at the Zagreb Jugoton store. Maybe someday I’ll pull it out from storage and compose a better Discogs entry.

Rachel M.

P.S. I also like being able to pull album cover images from the Discogs entries to use for my iTunes collection.

This post appeared on the EEFC listserv on Thursday, Sept. 11, 2014, as part of a conversation started by Dean Brown and is reprinted here with permission from the author. Rachel MacFarlane is the EEFC’s Workshop Manager and production manager of Kef Times.

UNESCO Reissues Continue: Algeria, Bali, Benin, Bulgaria, France, India, Pakistan, and Vietnam

UNESCO Collection’s 1983 “Bulgaria” recording is available for download or as a compact disc.

Just thought I’d pass along this notice I got from Smithsonian Folkways in Washington, DC. . . . and you can download the liner notes . . . hurray!

The Smithsonian Folkways reissue of two albums per week from the UNESCO Collection of Traditional Music continues! Read the latest guest blog posts, and check back weekly to explore musical traditions from around the world. Click here to find out more.

On September 19, Larry added the following comment for Kef Times:

The recordings were made in 1983 with the cooperation of both Balkanton and Bulgarian National Radio and most tunes were probably not released previously. The original liner notes (in English and French) are included as a PDF with the CD, or they can be downloaded here.

You can also use Smithsonian Folkways’ search engine to find other music of interest.

This post appeared on the EEFC listserv on Thursday, Sept. 11, 2014, and is reprinted here with permission from the author. Larry Weiner is a dance teacher and tapan player in Washington D.C. You can read an interview with him in the Fall/Winter 2001-02 Kef Times.

Russians and Caffeine

As a child, I grew up in a Russian Orthodox parish [in the U.S.] where many of the parishioners were deformed by WW I, the Stalin terror or WW II . . . eyes, parts of faces, missing body parts, that sort of thing. In many cases combined with the attendant psychiatry as well . . .

As a child, I grew up in a Russian Orthodox parish [in the U.S.] where many of the parishioners were deformed by WW I, the Stalin terror or WW II . . . eyes, parts of faces, missing body parts, that sort of thing. In many cases combined with the attendant psychiatry as well . . .

When I first became aware that the Americans had come up with decaffeinated coffee, this news came to me via the parish in the form that it was roundly judged to be “a communist plot to weaken America.”

It took me a few years to drill down to the reason for this view:

Coffee was considered to be the devil’s drink . . . barbarian . . . nothing like Russian tea. Pilgrims were occasionally scandalized, in going to Greek monasteries, to be offered this brew. However, during the WW I disaster, Russian troops frequently found themselves without medicine. The nurses and doctors quickly discovered that really strong coffee could keep some of the wounded from going into shock and dying. Hence, among the first two or three waves of the Russian emigration, coffee was considered a somewhat beneficial medicinal drink to strengthen the constitution, even though it had a dodgy foreign past.

This post appeared on the EEFC listserv on Mon, September 1, 2014, and is reprinted here with permission from the author. Alexander Eppler, a multi-instrumentalist who has taught kaval at the EEFC Balkan Music & Dance Workshops, is a flute maker in Seattle.

Dhimitrúla

D. Semsis, A. Tomboulis, R. Eskenazi (Athens, 1932) Photo: Wikipedia

Welcome to Kef Times’ first installment of Balkan Songs!

For this issue, we delve into the Balkan Tunes archive (specifically winter, 1994-95) [Ed. Note: Balkan Tunes was a newsletter Bill published in the 1990s that featured, well, Balkan tunes.] and emerge with “Dhimitrúla,” a song made famous by the Smyrneika singer Roza Eskenazi, pictured here.

In the 1990s, Miamon Miller and I, with help from Sophia Bilides, transcribed the tune and Sophia provided the translation.

“’Dhimitrúla’ is a song from the Smyrneika tradition (urban, early 1900s cabaret-style songs of the Greeks from Smyrna/Asia Minor),” writes Sophia. “It is attributed to the composer-musician Panayiotis Toundas and was recorded twice by Roza Eskenazi, first circa 1934, and again about 20 years later.”

Sophia recorded this song on her Greek Legacy CD; the the track and the full CD are available at cdbaby, Amazon.com and her website.

“I based my version on the 1934 recording,” Sophia writes, “in part because it featured the violí playing of the great Dimitrios Semsis, and because all the musicians at that session were in agreement on the rhythm, which is the old-style karsilamá (1-2 1-2-3 1-2 1-2). The later recording is a mess, rhythmically, with the musicians arguing instrumentally about whether to use the old-style karsilamá or the more common karsilamá rhythm which places the 1-2-3 at the end of each measure, which in the case of this particular song necessitated an extra beat as a fudge factor. (The ‘fudge mix’ has been carried over to contemporary versions of the song.)

“In addition to having a great sing-along chorus, Dhimitrúla is special to me because it’s one of the few songs I know of that actually mentions the word kéfi, that ‘frame of mind, a good mood or spirit, considered essential before the music-making can begin’—to quote my own liner notes.”

“In addition to having a great sing-along chorus, Dhimitrúla is special to me because it’s one of the few songs I know of that actually mentions the word kéfi, that ‘frame of mind, a good mood or spirit, considered essential before the music-making can begin’—to quote my own liner notes.”

From Bill: Our 1990s transcription and Sophia’s translation appear in the attached PDF. The last page of the PDF is an added version I did back in 2007 that actually combines the version the Greeks like to hear these days and the original version.

By the way, if any reader would like the piece in a different key, I would be happy to provide that; and also, if you use Finale, I would be happy to give you the original files, to use as you please—just email me.

Click here to hear the 1930s Roza Eskenazi version of this tune on You Tube

Click here for the PDF: Dhimitrula – musical transcription, translation, background.

Bill Cope is a multi-instrumentalist who began playing Balkan music in 1975 and teaching at the Balkan Music & Dance Workshops in 1982. He’s made numerous trips to the Balkans and has studied and performed with many noted players and singers. Read a profile about him in the Spring 2007 Kef Times.

Bill Cope is a multi-instrumentalist who began playing Balkan music in 1975 and teaching at the Balkan Music & Dance Workshops in 1982. He’s made numerous trips to the Balkans and has studied and performed with many noted players and singers. Read a profile about him in the Spring 2007 Kef Times.

Bill is editor of Kef Times’ Balkan Songs. If you have an idea and transcriptions, translation and background for an interesting song to be featured in a future issue, please contact him.

Balkan Songs

Welcome to Kef Times’ first installment of Balkan Songs. Each time this column appears, we will bring you musical notation, translation and background for a specific song.

For this issue, we delve into the Balkan Tunes archive (specifically winter, 1994-95) [Ed. Note: Balkan Tunes was a newsletter Bill Cope published in the 1990s that featured, well, Balkan tunes.] and emerge with “Dhimitrúla,” a song made famous by the Smyrneika singer Roza Eskenazi.

D. Semsis, A. Tomboulis, R. Eskenazi (Athens, 1932) Photo: Wikipedia

Welcome to Kef Times’ first installment of Balkan Songs!

For this issue, we delve into the Balkan Tunes archive (specifically winter, 1994-95) [Ed. Note: Balkan Tunes was a newsletter Bill published in the 1990s that featured, well, Balkan tunes.] and emerge with “Dhimitrúla,” a song made famous by the Smyrneika singer Roza Eskenazi, pictured here.

In the 1990s, Miamon Miller and I, with help from Sophia Bilides, transcribed the tune and Sophia provided the translation.

“'Dhimitrúla’ is a song from the Smyrneika tradition (urban, early 1900s cabaret-style songs of the Greeks from Smyrna/Asia Minor),” writes Sophia. “It is attributed to the composer-musician Panayiotis Toundas and was recorded twice by Roza Eskenazi, first circa 1934, and again about 20 years later.”

Sophia recorded this song on her Greek Legacy CD; the the track and the full CD are available at cdbaby, Amazon.com and her website.

“I based my version on the 1934 recording,” Sophia writes, “in part because it featured the violí playing of the great Dimitrios Semsis, and because all the musicians at that session were in agreement on the rhythm, which is the old-style karsilamá (1-2 1-2-3 1-2 1-2). The later recording is a mess, rhythmically, with the musicians arguing instrumentally about whether to use the old-style karsilamá or the more common karsilamá rhythm which places the 1-2-3 at the end of each measure, which in the case of this particular song necessitated an extra beat as a fudge factor. (The ‘fudge mix’ has been carried over to contemporary versions of the song.)

“In addition to having a great sing-along chorus, Dhimitrúla is special to me because it’s one of the few songs I know of that actually mentions the word kéfi, that ‘frame of mind, a good mood or spirit, considered essential before the music-making can begin’—to quote my own liner notes.”

“In addition to having a great sing-along chorus, Dhimitrúla is special to me because it’s one of the few songs I know of that actually mentions the word kéfi, that ‘frame of mind, a good mood or spirit, considered essential before the music-making can begin’—to quote my own liner notes.”

From Bill: Our 1990s transcription and Sophia’s translation appear in the attached PDF. The last page of the PDF is an added version I did back in 2007 that actually combines the version the Greeks like to hear these days and the original version.

By the way, if any reader would like the piece in a different key, I would be happy to provide that; and also, if you use Finale, I would be happy to give you the original files, to use as you please—just email me.

Click here to hear the 1930s Roza Eskenazi version of this tune on You Tube

Click here for the PDF: Dhimitrula - musical transcription, translation, background.

Bill Cope is a multi-instrumentalist who began playing Balkan music in 1975 and teaching at the Balkan Music & Dance Workshops in 1982. He's made numerous trips to the Balkans and has studied and performed with many noted players and singers. Read a profile about him in the Spring 2007 Kef Times.

Bill Cope is a multi-instrumentalist who began playing Balkan music in 1975 and teaching at the Balkan Music & Dance Workshops in 1982. He's made numerous trips to the Balkans and has studied and performed with many noted players and singers. Read a profile about him in the Spring 2007 Kef Times.

Bill is editor of Kef Times’ Balkan Songs. If you have an idea and transcriptions, translation and background for an interesting song to be featured in a future issue, please contact him.

Bulgarika: Horoto E Vechno

Longtime Balkan camp teachers Donka Koleva, Nikolay Kolev and Vassil Bebelekov team up with multi-instrumentalist Varna native Dragni Dragnev on a collection of 12 Bulgarian dance tunes that will get your toes a-tapping. Bulgarika is touring the U.S. this fall, so be sure to catch one of their shows if you can. If you aren’t lucky enough to see them live, Donka will gladly hook you up with a CD when the band returns from tour. Email her or call 646/296-4045 to place an order. Listen to track samples here.

Longtime Balkan camp teachers Donka Koleva, Nikolay Kolev and Vassil Bebelekov team up with multi-instrumentalist Varna native Dragni Dragnev on a collection of 12 Bulgarian dance tunes that will get your toes a-tapping. Bulgarika is touring the U.S. this fall, so be sure to catch one of their shows if you can. If you aren’t lucky enough to see them live, Donka will gladly hook you up with a CD when the band returns from tour. Email her or call 646/296-4045 to place an order. Listen to track samples here.

Theofania in Northern Greece: Men’s Dance Rituals of Blessing and Protection

Angelos Keras, the Arhigos (leader) of the Arapides in Monastiraki. (Spyros Taramigos)

At the southern edge of the Rhodope Mountains, skirts of rock sweep down to the Drama plain. In six tiny villages where mountain and valley meet, an ancient Twelfth Night tradition endures. On the 6th of January, Theofania (Epiphany), masked men in goatskins and sheep bells dance through the streets to dispel evil spirits, awaken the fertility of the earth and ensure a good year. These are the koudonofori, the bell wearers, also called Arapides, the Black Ones or Moors. Wrapped in goatskins, skin smeared with burnt cork as a sign of fire, they will dance at crossroads, at the cemetery, in the plateia (town square) and in front of each house, in a ritual of blessing and catharsis which has roots in age-old worship of Dionysus, god of fertility and wine.

Nikos Papadimitriou, an Arapis in Ksiropotamos. (Lenka Harmon)

Their preparation starts the day before, in the House of the Arapis in Monastiraki. This reclaimed ruin comes alive with the joy of friends and acquaintances greeting one another, sharing red wine and the traditional goat stew served free to all. All through the night dozens of musicians will play the pear-shaped Macedonian bowed lyra or kemene, and the daïre or defi, a large goatskin frame drum with metal jingles set into the wooden frame. These are the only instruments present (1), with a spine-tinglingly archaic sound whose effect is all the more hypnotic as the musicians play in unison. Even the singing is monophonic. My friends explain that this musical structure emphasizes old values of community solidarity, coherence and unity, in contrast to polyphonic ensembles where each individual instrument aims to make itself distinctly audible within the whole.

On the upper floor, tightly packed circles dance the same few dances over and over: the three-measure pattern in various styles and names (Teska, Ramna, Lekka, Hasapia); the simple Syrtos-type steps of Evzonikos and Levendikos, key dances on this occasion; and a few slightly more complex patterns such as Mantzourana, Pardales Kaltses (Tsourapia), Kori Eleni, the unusual local Paidouska in 3/4 time and the special antikrista steps once danced back and forth by young men and women facing each other on the threshing floor. As on all ritual occasions, the repetition of familiar simple patterns frees the dancers to focus on the inner work of raising good energy (kefi) to bless the community.

Arapides in Monastiraki. (Lenka Harmon)

The floorboards sway and sag alarmingly under our feet. The vigorous dance rhythms penetrate the very timbers of the house, as if to awaken the masks and furs waiting in adjacent rooms and in the cellar below. Enormous bells hanging from the beams are invisibly stirred into a faint, unearthly ringing. Carefully balanced atop the piles of furs, the tall conical goatskin masks in the otherwise empty rooms have such a presence, one glance at them instantly raises the hair on my skin. Soon, these articles of costume will transform ordinary men into fearsome Arapides, with the power to drive out the kallikantzari (goblins) and other mischievous spirits believed to wreak havoc during the twelve nights of Christmas. In the early hours of dawn, after dancing and drinking all night, the male celebrants help each other dress in the shaggy dark skins and towering conical masks. Surrounded by the deafening racket of heavy double bells swinging from their broad leather belts, and brandishing long wooden swords, the group—known as a tseta—appear fully capable of warding off the kallikantzari and any other potential danger.

Sacred Roles

It has always been men’s task to protect the community, and the phallic swords and headdresses leave no doubt that the Theofania customs are men’s rituals.

Pappoudes (Grandfathers) with lozenge-shaped amulets, and Gilinges (Brides) in Ksiropotamos. (Lenka Harmon)

However, the ability to give new life, to enter the realms of the dead, and to bestow the blessing of fertility are essentially women’s powers; to claim them, some of the men must dress as women. These are the Gilinges, or Brides. Further emphasizing the unspoken presence of feminine power, their costumes are rich in goddess embroideries, and all members of the party wear beaded amulets in the lozenge-shaped symbol of female fertility going back to Neolithic times. Goddess symbols are even stamped on many of the bells themselves. Wearing women’s clothing may be a means for men to gain temporary access to the realms of life and death, as when they visit the cemetery at sunrise to play the favorite songs of tseta members who have passed on, or to symbolically give birth to the life-affirming joy and kefi which bring renewal at this dark and hungry time of the year. Either way, this sacred cross-dressing has been known throughout Greece and the Balkans since the first Dionysian revelers of ancient times, and remains an essential element of the Theofania rituals.

Musicians and Tsoliades in Monastiraki. (Lenka Harmon)

As well as the Arapides and the Brides, the tseta includes the Pappoudes or Grandfathers, in Thracian men’s traditional dress; the Evzones or Tsoliades (soldiers) wearing short white fustanellas and the tsevres, a triangular shawl-like garment made of twelve large white kerchiefs sewn together on the diagonal, densely fringed with beads, sequins and colored threads, which the women tell me takes four months to prepare. There is also an occasionally appearing Bear, who some say represents ancient worship of the goddess Artemis. They journey together through the village, dancing at every single house throughout the day. The Arapides leap and stamp and swing their bells in an apotropaic din—this will indeed awaken the earth!—almost drowning out the massed sound of the lyras and daïres. The Evzones dance athletically, with energetic leaping turns whose momentum sends their short fustanellas sailing up to their waists, activating and emphasizing (so the Arhigos (leader) assures me) the fertile power of the male generative organs. In their hands, they twirl long, beaded snakelike kordonia (lanyards), which give power and definition to their dance movements and fulfill the ritual function of the handkerchief normally held by the lead dancer. At every house the entire tseta is rewarded with food and abundant drink, in the living tradition of sacred hospitality, which is seen as the most powerful reciprocal blessing of all.

The Whole Village Gathers to Dance

The great circle dance in the plateia of Monastiraki. (Lenka Harmon)

By three o’clock, the whole village gathers at the plateia to dance. Hundreds of people spiral into a single circle with one leader, keeping the large center open as a sacred space for the tseta to enact the ancient ritual dramas of death and resurrection, plowing and planting, the sacred wedding, stealing and rescuing the bride (2). The dancing goes on until dusk and then continues at a taverna for a second consecutive night.

That’s how it is in Monastiraki; each village enacts its own variation. In some places, children and women also participate in the Theofania rituals: in Ksiropotamos young girls in traditional costume dance through the village, while in Petrousa, all the daïre players are teenage girls, thirteen young women lined up like priestesses of Cybele from the time when the drummers were women. Here too, the villagers dance at crossroads, springs, sacred trees and finally around an enormous bonfire.

Cauldrons at the crossroads in Ksiropotamos. (Laura Shannon)

Fire is important in all the Theofania rituals. In the House of the Arapis in Monastiraki, the hearth fire will be kept burning for twelve nights and days, producing holy ash which will be used to bless people for the coming year. Cauldrons on open fires are a key part of the festivities everywhere, providing warmth and food for all comers, according to the hospitality of ancient tradition. In Petrousa, there is a special dance (Mayeiron, the Dance of the Cooks) in honor of these cauldrons, with an unusual symmetrical step pattern which focuses the energy or “fire” of the dancers in a particularly intense way.

Inner and Outer Fire

It is dark; it is snowing; I am here not as an observer only, but with friends, and so I surrender to the hours and days of drinking and dancing, feeling myself warmed and transformed by this inner and outer fire. As we circle the bonfire together, it seems to me that all of these fire-focused rituals hint at the unnamed presence of the goddess Hestia, whose domain is centered on the hearth, the source of light, warmth, food and all that is beneficial to the home. The nikokira, the lady of the house, was seen since ancient times as Hestia’s priestess. Her role is to tend the sacred fire through practical and ritual work and to literally focus its brilliance (estiazo, from Hestia, means “to focus”) so that it may bless the household and all its inhabitants. In ritual activities such as the Theofania, through the mediation of men dressed as women, this focused fire can be brought once a year from the private space of the home—the realm of the women—into the public space of the village, the realm of the men. This union of men’s and women’s fertile powers is the holy spark of blessing which ensures health, wealth, happiness and abundance for all in the coming year.

Laura Shannon © 2014

Hospitality to strangers in Ksiropotamos. (Lenka Harmon)

Footnotes:

(1) In Monastiraki, Ksiropotamos, Petrousa, and Pyrghi, the lyra and daïre are played, while in Volakas and Kali Vrysi it is the daïre and gaïda (bagpipe). Only in Monastiraki, on other occasions, have I sometimes heard all three instruments played together.

(2) These same dramatic elements appear in other Greek ritual customs performed either at Theofania or during Carnival, including the Kaloyeros of Ayia Eleni, Karnivalia of Sohos, Baboyeroi of Flambouro, Tsekekia of Pondismeno, Boules of Naoussa—all of which I have had the privilege of witnessing in the incomparable company of Yvonne Hunt—and in the Bulgarian Survakari and Kukeri rituals and other customs found throughout the Balkans and Central Europe as far as the Swiss Alps.

Thanks to: Katerina Asteriou-Kavazi, Nikos Papadimitriou, Angelos Keras, Kyriakos Moisidis, Panayiotis Zikidis, Yvonne Hunt, and to Spyros Taramigos and Lenka Harmon for permission to include their photos.

References:

Aikaterinidis, Georgios. “Αραπήδες: Ενα Ευετηρικό Δρώμενο στο Μοναστηράκι Δραμας,” Morfotikos kai Politistikos Syllogos Monastirakiou Dramas (1998)

Barber, E.W. The Dancing Goddesses (2014)

Hunt, Yvonne. Traditional Dance in Greek Culture (1996)

Kelly, Mary. Goddess Embroideries of Eastern Europe (1996)

Lawson, John C. Modern Greek Folklore and Ancient Greek Religion (1964)

MacDermott, Mercia. Bulgarian Folk Customs (1988)

Papoutsis, Aikaterinidis, Papakostas, et al. “Λαικά Δρώμενα και Αρχέγονες Τελετουργίες.” Kentro Politistikis Anaptyksis Anatolikis Makedonias (2010)

Prantsidis, Yiannis. Ο Χορός στην Ελληνική Παράδοση και η Διδασκαλία του. Aikdotiki Aiginiou

Redmond, Layne. When the Drummers Were Women (1997)

Shannon, Laura. “Womenʼs Ritual Dances: An Ancient Source of Healing in Our Time,” in Dancing on the Earth, eds. J. Leseho & S. McMaster. Findhorn Press (2011)

Shannon, Laura. “Ritualtanz in Griechenland, Damals und Heute.” Neue Kreise Ziehen (2011)

Tomkinson, John. Festive Greece: A Calendar of Tradition (2003)

Laura Shannon began attending Balkan camps in the late 1980s. She teaches Greek, Balkan and Armenian dance throughout Europe, North and South America and Australia, and since 2005 has been based in Greece researching village dance traditions. She is on the faculty of the Sacred Dance Department at the Findhorn Foundation in Scotland and is currently pursuing a master’s degree in Mythology and the Sacred at the University of Canterbury (UK). www.laurashannon.net

Laura Shannon began attending Balkan camps in the late 1980s. She teaches Greek, Balkan and Armenian dance throughout Europe, North and South America and Australia, and since 2005 has been based in Greece researching village dance traditions. She is on the faculty of the Sacred Dance Department at the Findhorn Foundation in Scotland and is currently pursuing a master’s degree in Mythology and the Sacred at the University of Canterbury (UK). www.laurashannon.net