Mark Forry

Likely to be spotted with mouth open wide, leading a tamburica ensemble and often knowing more lyrics than anyone else in the room, Mark Forry has been involved in Balkan camps since the 1975 Sweet’s Mill camp (a precursor to the EEFC camps). Since 1981, he has frequently taught at the EEFC’s Mendocino or East Coast workshops, usually teaching singing or tamburica ensemble and leading group sings.

Mark Forry remembers his first taste of the Slavic music that would become such a beacon in his life. It was in the summer of 1974, when he was completing his studies at the University of California-Santa Cruz, where he had a dual major in music (bassoon and piano) and dance (mostly modern).

“One of my college roommates came back from the Center for World Music in Berkeley saying, ‘We just learned this great music!’” Mark remembers. The scheduled Turkish musicians for the workshop hadn’t gotten their visas and instead two students, Mark Levy and Lauren Brody, volunteered to teach Bulgarian music. His roommate played a record she’d heard there (the first Nonesuch Music of Bulgaria) and another of Mark’s roommates said, “I used to dance to that music at my Jewish summer camp.”

Mark liked the idea of “this cool music that you could dance to.” He started going folk dancing in Santa Cruz.

“What got me about the music were the rhythms and scales,” Mark says. As a music student he already loved Stravinsky and Central European composers such as Bartók and Janáček. Now he was drawn to the rhythms and harmonization of Bulgarian music as well. He even got to experiment with a village instrument when David Kilpatrick, a newly hired UCSC ethnomusicologist who had spent time in Greece, loaned him a zurna.

Music Done by Everybody

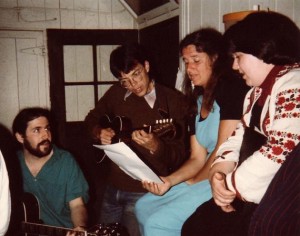

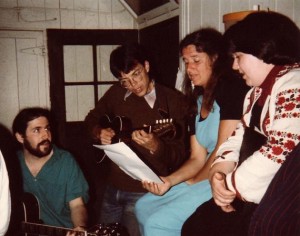

Playing brač at Mendocino in the 1980s.

For two different blocks of time, once before graduating from UCSC and once after, Mark went to Cleveland, originally to study modern dance and bassoon. He went folk dancing there and soon met Walt Mahovlich and began playing kaval and tapan for Macedonian gigs with him. Also through Walt, Mark started dancing with the Croatian group Slava. At one concert, Slava was performing a Croatian suite and the tamburica group’s bass player didn’t show up. Mark not only figured out how to play the bass parts that afternoon but also learned his first two tamburica songs: “Sliku tvoju ljubim” and “Osman Aga.”

When Ethel Raim came to Cleveland and Mark attended a workshop she gave on Balkan singing, Mark says, “I discovered that I had a big voice.” In addition, he says, one of his modern dance teachers insisted that her students do vocalizations with their exercises, which helped him free his natural voice.

“The more I got into it,” he says, “I was just thrilled by the idea of community music, music done by everybody.”

Mark had grown up in a close, Anglo-American community in the East Bay (San Francisco Bay Area). People liked and respected music—Mark’s parents certainly loved music and supported him in his classical music pursuits—but music was in a different category from everyday life. It was not a central part of weddings, parties and other important events.

But for Mark, it was already becoming more important. A student of classical music, he also played guitar in rock-and-roll garage bands and “sit around the campfire” settings.

Music: Essential to Who We Are

“Growing up near San Francisco in the ’60s,” he says, “music was really important to who we were and our culture. I was thrilled to find with the Croatians, Serbians, Macedonians, Hungarians and Slovenians I met in Cleveland, music wasn’t just an ‘oh, by the way’ kind of thing. It was essential to who they were and how they made community and bonded with each other. As a musician, I was charmed and thrilled by that.”

He also loved the variety of ethnic experience he encountered in Cleveland. In the Bay Area, the ethnic areas he had known had been Asian and African American. In Cleveland he found a myriad of ethnic neighborhoods—Slovenian, Croatian, Hungarian, Romanian and more—each one with its own music and dance groups, social halls and picnics.

While in Cleveland, Mark became captivated by the idea of pursuing ethnomusicology. After two winters in Cleveland, he moved back to California with the intention of starting grad school at the University of California-Los Angeles.

But before moving to L.A., he lived for about a year in Berkeley, where he sang with the Balkan chorus Danica, played Bulgarian and Macedonian music with Stewart Mennin, and played Croatian music with Frank Dubinskas. He also heard his first Georgian singing, another flavor that would become a lifelong interest.

With Aman in the late ’70s.

Once in L.A. and studying ethnomusicology, Mark continued his involvement with international folk dancing and Balkan music. He started playing in the UCLA Balkan Music Ensemble led by Jane Sugarman and Mark Levy. (He also performed in the Korean and Persian ensembles, playing kayageum and tar, respectively.) He got to know Michael Alpert and the musicians of the group Pitu Guli, organized by Mark Levy, which rehearsed weekly and served as staff at the early Balkan camps. He started taking Yugoslav dance classes with Elsie Dunin, who also involved him with her research projects and encouraged his interest in Croatian and Serbian cultural life in L.A.

Soon he was playing and singing in the folk dance performing ensemble Aman as well as the short-lived ensemble El Conjunto Strandzhansko, later dubbed Meden Glas (Honey Voice; Michelle Breger, Cindy Burton, Bill Cope, and Mark, occasionally with Ed Leddel; Bulgarian music). He also played bass with the Tisza River Valley Boys (Miamon Miller, Don Sparks, Jim Knight and Mark, with Deanne Hendricks singing; music from Serbia, Hungary, Romania and Slovakia). Mark started getting serious about tamburica music—more on that below. And he started attending Balkan camp in Mendocino.

Early Mendocino Camps

Playing accordion at Mendocino in the 1980s as Nestor Georgievski sings.

“It was a rich time,” he says, referring to the first Mendocino camps. “We were all young. Those times in your life are cemented in your memory forever—discovering other people crazy about the same beautiful obscure music that you were, and finding each other in this beautiful place in the redwoods.”

There was also a countercultural aspect to this fascination, he says, especially at the beginning.

“All that I had hoped for, all the promise of the Counterculture and the Revolution, returning to a set of values, it was offered to us in some way. There was the hope that we’ve arrived in this beautiful, magical place; by gosh, we’re going to live here the rest of our lives! One of our friends, I think it was Michael Alpert, used to say that going to Mendocino is like going to Brigadoon: it’s a magical place that materializes once a year and then it’s gone. But the hope for me and maybe for others was that it wasn’t just once a year. This was our reality. There was something really hopeful and positive about it.”

Mendocino ’78 kaval class.

Over the years Mark’s teaching at the workshops has included singing, in which he has presented, at different times, songs from Bosnia, Bulgaria, Croatia, Montenegro, Serbia and even Hungary; Dalmatian klapa singing; and tamburica ensemble. He also taught beginning Bulgarian kaval in the days before teachers from Bulgaria came to camp.

Deeper into Tamburica Music

To complement his ethnomusicology studies, Mark started studying Serbo-Croatian and Hungarian. In 1978 he got a language study grant to attend a Slavists’ gathering in Belgrade—a three-week language and literature seminar with teaching and cultural activities. He took the opportunity to travel around Yugoslavia, attending a session of the Badija summer folklore school in Croatia and taking buses and trains around the country, looking for musicians of various sorts and buying “piles and piles of LPs.”

Back in L.A., Mark worked as both a teaching assistant and a research assistant in the ethnomusicology archive at UCLA where, among other things, he was able to find amazing resources for Georgian music. “At the time, it was next to impossible for Americans to get to Georgia,” he says.

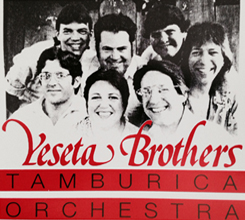

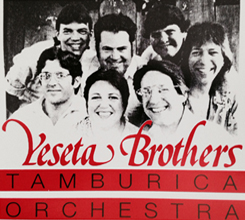

He also started spending more and more time in the Serbian and Croatian communities in the area. St. Steven’s Serbian Orthodox Church had a tamburica orchestra led by Nikola Bakajin and Dragutin Mijatović, accomplished tambura players from Vojvodina, with whom Mark started studying tambura more seriously. (By the way, in Bosnian-Serbian-Croatian, the word “tambura” is the generic name for the instruments in a tamburica orchestra; in Bulgarian and Macedonian, “tambura” generally refers to the long-necked lute used in those countries. Throughout this article, the term is used with the former meaning.) In the Aman Ensemble’s tamburica band, which was directed by Chris Yeseta, Mark learned even more technique and repertoire. His connection with Yeseta, one of four musician brothers, eventually led to the opportunity to play in the big tamburica ensemble “Croatia” at St. Anthony’s Croatian Catholic Church and, later, with the smaller Yeseta Brothers Orchestra, with whom Mark still plays when he’s in town.

He also started spending more and more time in the Serbian and Croatian communities in the area. St. Steven’s Serbian Orthodox Church had a tamburica orchestra led by Nikola Bakajin and Dragutin Mijatović, accomplished tambura players from Vojvodina, with whom Mark started studying tambura more seriously. (By the way, in Bosnian-Serbian-Croatian, the word “tambura” is the generic name for the instruments in a tamburica orchestra; in Bulgarian and Macedonian, “tambura” generally refers to the long-necked lute used in those countries. Throughout this article, the term is used with the former meaning.) In the Aman Ensemble’s tamburica band, which was directed by Chris Yeseta, Mark learned even more technique and repertoire. His connection with Yeseta, one of four musician brothers, eventually led to the opportunity to play in the big tamburica ensemble “Croatia” at St. Anthony’s Croatian Catholic Church and, later, with the smaller Yeseta Brothers Orchestra, with whom Mark still plays when he’s in town.

Experiences like these gave Mark fodder for his master’s thesis on tambura music in the U.S.: The Bećar Music of Yugoslav-Americans (1982). By this time he was teaching singing in settings as diverse as ethnomusicology conferences, a cappella festivals and folk dance camps.

In 1983-84 Mark embarked on a 15-month fieldwork project in Yugoslavia, focusing on tambura music in Vojvodina. That fieldwork eventually gave rise to his Ph.D. dissertation, The Mediation of “Tradition” and “Culture” in the Tamburica Music of Vojvodina (Yugoslavia) (1990).

Moving Back North

In 1988 Mark moved back to Santa Cruz, where he worked in various jobs, including serving as a research assistant for Mickey Hart (Grateful Dead drummer) and as arts administrator for Tandy Beal and Company (an internationally known dance company; Tandy Beal has attended the EEFC workshops). Mark was focusing on finishing his dissertation, but also found time to play kaval and record with the Santa Cruz-based, all-female-until-he-came-along Balkan band Medna Usta.

![Mark and Esma Redžepova at East Coast Camp, [YEAR??]](https://keftimes.org/wp-content/uploads/KT-2014_fall_mf_slider2-300x132.jpg)

Mark and Esma Redžepova at East Coast camp, 1998.

A Fulbright post-doc took him to Yugoslavia again in 1990. This time he lived in Zagreb and focused on tambura in Croatia, but kept in touch with friends and colleagues in Vojvodina. Upon his return, not finding an academic job, he signed up for temporary work doing data entry and ended up working for a UNIX company on a technical publications project. He has worked for technology companies ever since.

In the 2000s Mark continued to play with the Yeseta Brothers in Southern California and performed with his own ensemble, Zapadne Lole (later Mark Forry and Friends), in Northern California, while continuing to teach at camps, workshops and festivals. He taught for Village Harmony camps, a teen touring camp in the U.S. and two adult camps, one in the U.S. and one in Bosnia. The experience revived his interest in Georgian music and he started studying the language, ran a “self-help Georgian singing group” in Santa Cruz, and traveled to Georgia in 2008.

In 2011 Mark was inducted into the Tamburitza Association of America Hall of Fame. (Joseph L. Kroupa)

In 2011 he was inducted into the Tamburitza Association of America Hall of Fame, and his translated dissertation was published in Novi Sad (Serbia).

In Hungary

Mark is now living in Baja, Hungary, 30 kilometers from the Serbian border. He lives with Zsuzsa Farkas, whom he met in Novi Sad in 1983.

“My job is portable; I am still employed in Silicon Valley,” he says. “Zsuzsa is an arts teacher here.” Mark lives in Hungary most of the year and goes to California for work and to catch up with family and friends four times per year.

“I live in southern Hungary, where there are a lot of South Slavs, mostly Bunjevci, some other Croatians and a smaller number of Serbians,” he says. “There’s a tradition of tambura music in Hungary that goes back quite a ways.” He sits in occasionally with a couple of Bunjevac groups locally.

(Photo: John Daly)

“It is nice to see, after all that happened during the war, especially in Eastern Croatia and Slavonia, that there remains a lot of contact between musicians. There’s a big festival in Novi Sad that I’ve been involved with and it’s good to see that there’s Croatian representation there. That festival features many small ensembles, kafana or wedding bands, working musicians who play for parties, and also people looking to preserve local traditions, such as Serbs from Romania or Austria or Montenegro. And there is music being written for large tambura orchestras, not only in Croatia but for the Croatian and Serbian communities in surrounding countries—Austria and Hungary and Romania and elsewhere.”

Thoughts About the EEFC Workshops

Playing saz at the 2010 Mendocino workshop with Jesse Manno, James Hoskins, Bob Beer and a host of frame-drum players. (Barbara Saxton)

One significant change Mark has seen in the workshops pertains to men’s singing. “In the late ’70s and early ’80s, we had all these great women teaching that phenomenal women’s repertoire at camp,” he says. “But at the time, nobody was really teaching the men singing. Michael Alpert came occasionally and Lorin Sklamberg (lead vocalist for the Klezmatics) came one year. But now, he says, with Dragi Spasovski, John Morovich, Christos Govetas, Ljuba Živkov and others, “it’s phenomenal for men who want to sing.

“I think the EEFC is going in a great direction,” he adds. “It’s really exciting to see more and more younger people involved. I feel like we really got past what has been a stumbling block for a lot of cultural organizations: how do you take the vision and passion of our founders and turn it into something sustainable? That’s a real credit to Mark [Levy] and Carol [Silverman] , and to everybody else who’s stepped up in the meantime.

“All those things we enjoyed when we were in our 20s—now there have been two subsequent generations of people in their 20s coming to camps. There’s a strong desire on the part of everybody involved to keep it viable.”

You know when it’s January? And you haven’t seen the sun since September? And the long, grey spring stretches out ahead of you with that little twinkle called Balkan camp at the end of the tunnel? And everybody else is partying out at Golden Fest? Every year at that time we would think, we really need to have something like Golden Fest that we can go to! In our town!

You know when it’s January? And you haven’t seen the sun since September? And the long, grey spring stretches out ahead of you with that little twinkle called Balkan camp at the end of the tunnel? And everybody else is partying out at Golden Fest? Every year at that time we would think, we really need to have something like Golden Fest that we can go to! In our town! We got the hall, arranged for the Seattle Junior Tamburitzans to run the kitchen and bar, crossed our fingers and did it. We remember when we opened the doors at the first Balkan Night—the hall was full from the 4 p.m. start time; it was like stepping on a conveyer belt that was running a little bit too fast, but in a great way. Everyone was so thrilled and excited by what was happening, and we are just trying to keep that feeling continuing.

We got the hall, arranged for the Seattle Junior Tamburitzans to run the kitchen and bar, crossed our fingers and did it. We remember when we opened the doors at the first Balkan Night—the hall was full from the 4 p.m. start time; it was like stepping on a conveyer belt that was running a little bit too fast, but in a great way. Everyone was so thrilled and excited by what was happening, and we are just trying to keep that feeling continuing. BNNW was held at the Russian Center in 2012 and 2013. In 2014, it moved to St. Demetrios Hall and we expect to keep it there. Dates have ranged from as early as February 21 (scheduled for 2015) to as late as March 16. Why the roaming dates? We are trying to keep it on the weekend of Apokries (Orthodox Mardi Gras). That way, all the Kukeri and Babouyeri (traditional Balkan mummers) make sense!

BNNW was held at the Russian Center in 2012 and 2013. In 2014, it moved to St. Demetrios Hall and we expect to keep it there. Dates have ranged from as early as February 21 (scheduled for 2015) to as late as March 16. Why the roaming dates? We are trying to keep it on the weekend of Apokries (Orthodox Mardi Gras). That way, all the Kukeri and Babouyeri (traditional Balkan mummers) make sense! Another part of our motivation is to inspire and support young people to play Balkan music, so we take whatever proceeds we make to fund scholarships to the Mendocino Balkan Music & Dance Workshop and balkanalia!. It takes a lot of work and support from community members to pull this off, and thankfully, people have been willing to work hard and help by volunteering at the festival. So far we have been able to fund three full scholarships to the Mendocino Balkan Music & Dance Workshop, and seven scholarships to balkanalia!.

Another part of our motivation is to inspire and support young people to play Balkan music, so we take whatever proceeds we make to fund scholarships to the Mendocino Balkan Music & Dance Workshop and balkanalia!. It takes a lot of work and support from community members to pull this off, and thankfully, people have been willing to work hard and help by volunteering at the festival. So far we have been able to fund three full scholarships to the Mendocino Balkan Music & Dance Workshop, and seven scholarships to balkanalia!. Each year we bring in a featured band from a specific region, and present a separate event the following night that just focuses on that band. This year we brought Kalin Kirilov and his group, and on the night after Balkan Night, the local Bulgarians put together an amazing evening of games and rituals that was delightful and meaningful. The year before, we brought Merita Halili and Raif Hyseni, and they sold out the Triple Door, full of Albanians from all over Albania—it was just electrifying!

Each year we bring in a featured band from a specific region, and present a separate event the following night that just focuses on that band. This year we brought Kalin Kirilov and his group, and on the night after Balkan Night, the local Bulgarians put together an amazing evening of games and rituals that was delightful and meaningful. The year before, we brought Merita Halili and Raif Hyseni, and they sold out the Triple Door, full of Albanians from all over Albania—it was just electrifying!

Musician, singer and teacher John Morovich specializes in the folklore of Croatia. He is artistic director of the Seattle Junior Tamburitzans, and Ženska Klapa Ružmarin. He performs regularly with the Sinovi Tamburitzans, a group he co-founded in 1979. He has created dozens of choreographies, scores for tamburitza orchestra and choirs, and has taught regularly at EEFC camps since 1987.

Musician, singer and teacher John Morovich specializes in the folklore of Croatia. He is artistic director of the Seattle Junior Tamburitzans, and Ženska Klapa Ružmarin. He performs regularly with the Sinovi Tamburitzans, a group he co-founded in 1979. He has created dozens of choreographies, scores for tamburitza orchestra and choirs, and has taught regularly at EEFC camps since 1987.

He also started spending more and more time in the Serbian and Croatian communities in the area. St. Steven’s Serbian Orthodox Church had a tamburica orchestra led by Nikola Bakajin and Dragutin Mijatović, accomplished tambura players from Vojvodina, with whom Mark started studying tambura more seriously. (By the way, in Bosnian-Serbian-Croatian, the word “tambura” is the generic name for the instruments in a tamburica orchestra; in Bulgarian and Macedonian, “tambura” generally refers to the long-necked lute used in those countries. Throughout this article, the term is used with the former meaning.) In the Aman Ensemble’s tamburica band, which was directed by Chris Yeseta, Mark learned even more technique and repertoire. His connection with Yeseta, one of four musician brothers, eventually led to the opportunity to play in the big tamburica ensemble “Croatia” at St. Anthony’s Croatian Catholic Church and, later, with the smaller Yeseta Brothers Orchestra, with whom Mark still plays when he’s in town.

He also started spending more and more time in the Serbian and Croatian communities in the area. St. Steven’s Serbian Orthodox Church had a tamburica orchestra led by Nikola Bakajin and Dragutin Mijatović, accomplished tambura players from Vojvodina, with whom Mark started studying tambura more seriously. (By the way, in Bosnian-Serbian-Croatian, the word “tambura” is the generic name for the instruments in a tamburica orchestra; in Bulgarian and Macedonian, “tambura” generally refers to the long-necked lute used in those countries. Throughout this article, the term is used with the former meaning.) In the Aman Ensemble’s tamburica band, which was directed by Chris Yeseta, Mark learned even more technique and repertoire. His connection with Yeseta, one of four musician brothers, eventually led to the opportunity to play in the big tamburica ensemble “Croatia” at St. Anthony’s Croatian Catholic Church and, later, with the smaller Yeseta Brothers Orchestra, with whom Mark still plays when he’s in town.![Mark and Esma Redžepova at East Coast Camp, [YEAR??]](https://keftimes.org/wp-content/uploads/KT-2014_fall_mf_slider2-300x132.jpg)