Merita Halili and Raif Hyseni.

Singer Merita Halili and accordionist/composer Raif Hyseni, world-class performers from Albania and Kosova, respectively, began teaching at the EEFC camps in 1997. Merita captivates students with her extraordinary vocal range, filigree-like ornamentation, knowledge of regional styles and heartfelt approach. Raif inspires with his virtuosic playing, innovative arrangements and humor. At Balkan camp they often intertwine the Albanian singing class with the Albanian/Kosovar instrumental ensemble class to create unforgettable music and learning.

Singing like a bird

Merita Halili was born in Tiranë, the capital of Albania. She was the youngest in the family and the only girl, with six older brothers. One of her earliest memories is of being in a play at the age of 5 at day care. “I had to sing in a cage, wear a bird costume and look like a bird,” she says. “I don’t remember the song but I remember that when they opened that cage and I came out in the bird clothes, all the teachers said I sang so beautifully.”

At home, music was always present. Her mother had a beautiful voice and the whole family sang; when people would come over, it was customary after lunch or dinner to sing together—folk songs or popular songs of the day.

During elementary school Merita participated in the local Young Pioneer group, which sang at festivals. That was the beginning of her musical training. By the time she was in fourth grade, her teachers at school started taking her to other schools to serve as an example in singing class to help teach other children to sing.

Merita in concert around 1982-83.

Later she auditioned for and was accepted into music high school, where the teaching was at a level comparable to college in the U.S.—highly professional and very difficult. She trained in classical music, including opera. On the side, Merita participated in two amateur folk music groups, Ensemble Tirana and Ensemble Migjeni. In 1983, she attended the Gjirokastër National Folklore Festival, a prestigious festival that takes place every five years in southern Albania. Representing her home city, the capital, she performed a difficult song, “Dore për dore,” and received an award.

Merita excelled at operatic singing and performed a 1.5-hour concert for her recital at the age of 16. It was unclear whether she should pursue a career in classical opera or folk music. But before she could finish high school, the State Ensemble for Folk Songs and Dances snatched her, hiring her as a soloist because of her unique voice.

“I wasn’t disappointed [to leave a classical opera path],” Merita says. “I was confused in the beginning, but being hired by the ensemble felt very prestigious. The State Ensemble was the highest-ranking cultural institution in Albania at that time—the very top. Working there would allow me to travel outside the border, which was a big deal at that time. I would be able to represent our country to people in other countries.”

She toured with the ensemble in Europe until 1989. Soon after she left the ensemble, communism fell and everything changed. In 1991, when Merita was invited to sing at a wedding for someone she knew in America, she got a visa and went.

We’ll catch up with Merita in the U.S. presently . . . but first, let’s backtrack and look at Raif’s story.

“I want one son to be an accordion player.”

Raif Hyseni is from the Republic of Kosova, which has a large Albanian majority. He grew up in Mitrovicë, the oldest of five children—three boys and two girls.

“When my father was a young man,” Raif says, “he had a conversation with himself. He said, ‘If I get married some day, I would love to have at least two sons. Why? One to be an accordion player and the other one to be a pilot.’”

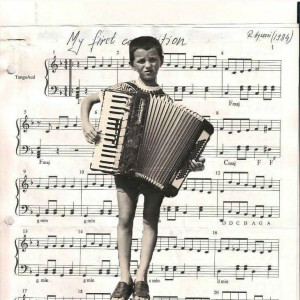

Raif as a 4th grader with his first personal accordion, 1975. He kept this instrument until the war, when it was stolen, along with the family’s other possessions, by occupying military forces, who then burned the apartment.

One day when Raif was in fourth grade his father came home from work and told Raif he was going to sign him up for music school. Raif didn’t want to go. His main interest at the time was the movie star Bruce Lee; he asked if he could go study martial arts instead. His father said no.

Music school was a separate school held in the afternoon, after the regular elementary school day. The school offered instruction in Western classical music on various instruments, singing and choir. Raif loved the music but expected to be able to play fast, challenging tunes right from the beginning. Instead, he was assigned “boring” exercises, like having to hold each note of the scale as a whole note for the count of four.

After a few months, he quit the elementary music school because he found the exercises so boring (his father wasn’t pleased), and continued trying to learn to play accordion on his own. But after three or four months, Raif says, “something clicked in my mind and I asked my father to please send me back to music school. He did, and since then I’ve never stopped.” (By the way, Raif and all his siblings finished elementary music school, but he is the only one who continued with music. One of his brothers did, indeed, pursue studies and pass all his tests to become a pilot, although due to various factors, some of them political, he did not actually become one.)

“It’s a big difference."

Raif loved folk music. He mused about the differences between playing music at school versus the folk band wedding musicians he had seen: at school, it was just your teacher, yourself and a musical score in front of you. But at a wedding, there was folk music, dancing, food and drink. “People are happy,” he said. “It’s a big difference.”

By the time Raif was in high school, he knew he wanted to do music as a career. He started playing in different folk bands and orchestras, always as the youngest member. One of those bands was Hasan Prishtinë and another was Rilindja. With these ensembles, while still in high school, he toured in Germany, Austria and many states in Former Yugoslavia.

Raif pauses for a laugh during his accordion class, Iroquois Springs, 2011. (photo: Margaret Loomis)

After high school, Raif enrolled in the Academy for Performing Arts at the University of Kosova in Prishtinë, attending college in the mornings and working as a high school music teacher in the afternoons. Around that time, Isak Muçolli, first violinist of the Radio Television of Prishtinë (RTP) Symphonic Orchestra, snagged Raif to play accordion with that orchestra. “It was my dream,” Raif says. “Being invited to play with Isak Muçolli was like being invited to play with Paganini.” He appeared with the orchestra on radio and television and had the opportunity to accompany some of the top singers in Kosovo and Macedonia.

He also started playing with a young group called Besnikët that became very successful—a superstar group, comparable, he says, to the Backstreet Boys. Popular internationally on radio and TV, they toured in Kosova, Macedonia and Montenegro, selling out concerts wherever they appeared—even 5,000-seat halls.

In 1989, when Raif was a third-year student, the Albanian community in New Jersey hired Besnikët to perform in a restaurant in North Bergen, N.J., for six months. They paid for his airfare and room and board during the engagement, so he left his teaching job and came to the U.S. on a temporary work visa. His position back home was to be held for a one year.

Within two months after Raif’s departure, the Milošević regime began shutting down institutions in Kosova, including the academy where Raif was still enrolled as a student. Albanians in all institutions were laid off their jobs, including Raif’s father; many university professors, teachers and political activists, including musicians and performers, were sent to prison.

“I had a wonderful life back in Kosova,” Raif says. “I wanted to go back to Kosova and hoped that the situation would change for the better.” He headed back to Kosova in May 1990, after Besnikët completed its six-month contract. But given the upheaval in Kosova, he came back to the U.S. about six months after that.

Playing for an outdoor dance line, Iroquois Springs, 2009. (photo: Margaret Loomis)

Meeting in America

Merita had been performing in New York for a few months. Her friends were worried about her, since she was a professional and needed someone at a high level to accompany her. Then, one night in 1991, she attended a concert in Staten Island as a guest artist. Raif was playing in the band and was asked to accompany her.

“I had heard about him and his talent, and that he had recorded with famous singers in Kosova,” she said. They arranged a meeting and every song she asked him about, he knew. “It was really, really good,” she says. “After that I fell in love with him. First I was attracted by his talent, then we were attracted to each other. It was luck.”

Later that year the couple headed back to Europe and lived in Belgium for several months, then Switzerland for about 6 months, performing for Albanian communities in Belgium, Germany and Switzerland. Later, amidst increasing political tensions in the area, they lived in Albania for more than three years, performing in Macedonia and, later, Sweden and Germany.

In 1994, Merita took part in a 12-week televised festival and competition sponsored by the Albanian state television featuring singers from all over Albania and the Albanian diaspora and evaluated by a jury of European judges. Of the 100 singers competing, Merita was awarded first place, accompanied by a prize of $10,000, and received the prestigious award of “National Ambassador” from the President of Albania.

Raif and Merita at Balkan camp, 2012. (photo: Margaret Loomis)

She and Raif had not planned to come back to the United States. But because of the political situation, the war in Bosnia and Croatia, the change of Albania’s system from communism to democracy, and steadily worsening conditions in Kosova, they made the decision to move to the U.S. and “start from the beginning.” They moved to Caldwell, N.J., in 1995.

After that, the situation in Kosova became even worse, with war breaking out in 1998. For about two months there was no communication from anyone in Raif’s family, while the headlines blared horrific details about the ethnic cleansing happening in Kosova. Eventually Raif’s parents and brothers were able to get to safety in Tiranë, in Albania, where they stayed with Merita’s family.

“It was very difficult for us because we are very close to our family, and they are back there,” Merita says. “I don’t consider myself an immigrant, but leaving Albania as a famous singer it was very hard for me. My community here likes me, and they hire Raif and his band and me all the time, but it wasn’t like what I left in Albania.”

Life in New Jersey

Now Merita is pursuing her studies to become a licensed music teacher in the school system. “I really enjoy teaching,” she says.

From L: Polly Tapia Ferber, Merita with daughter Engji, Jerry Kisslinger, Alan Zemel, Michael Ginsburg and Raif at Balkan camp, Ramblewood, 1998.

She and Raif perform around the region and the country at festivals and community weddings. They usually travel with five instrumentalists; for a local wedding, six or seven instrumentalists. Raif serves as the manager.

"Back in Kosova and Albania, there were institutions—the opera or the folk ensemble—that organized the concerts,” he says. “Our job was just to decide what repertoire to perform and to give those tunes to the band leader; he would arrange rehearsals. We didn’t have to deal with the tickets, how many people will show up, the sound system, who’s going to be our makeup artist, how we will get there, who will perform. Here, we have to substitute that institution with one person. It’s not easy, because we want to do the best.” They feel fortunate that Ethel Raim, Artistic Director of the Center for Traditional Music and Dance (who, by the way, taught singing at one of the earliest U.S. Balkan camps—Sweet’s Mill, around 1975), has connected them to opportunities to perform on some of the best stages in the area.

One year (2012) the Albanian Ensemble got into the spirit sartorially as well as musically.

Raif completed his bachelor’s degree in music from Caldwell University, then earned a master’s in music from Montclair State University. He has stayed at the university, working as an adjunct professor of music. He wrote a curriculum and got it approved to teach Albanian music, and the Balkan-Albanian Ensemble he directs is the first of its kind at a university. In recent course evaluations, one student wrote, “Many of the teachings here are able to be applied across multiple platforms into classical music playing, jazz music playing, and a different approach to a teaching method.” Another stated, “This [ensemble] has helped me to grow both as a learning musician and an overall lover of music.”

In addition, Raif has composed and arranged dozens of songs and instrumental melodies for accordion, and has written music for plays and documentary films. He is currently working on a CD project that includes his own compositions and traditional folk tunes, and features many musician friends. “I don’t know when we will be able to finish it,” he laughs. “I have high standards.”

At home the family speak Albanian and English. Raif and Merita have three daughters: Megi, 27; Engji, 20; and Rea, 13. The older girls played music as children but now Megi is a teacher and Engji is working to become a dentist.

Megi, Engji and Rea. (photo: Margaret Loomis)

“I like singing like my mom,” says Rea, who has been playing violin since first grade and is already an accomplished singer. “I think folk music is very fun; it’s upbeat. It excites you. At camp, when people play folk music, everybody gets excited and dances.”

Experiencing Balkan camp

“I was very, very surprised,” Merita says, when asked about her first Balkan camp. “What kind of place was this? I had never seen people together so fascinated for Balkan music. What were they doing with this music? What attracted them to it? And, oh, my God, how should I represent my music?” Starting with Jane Sugarman as her translator, she plunged in. (Jane is a Balkan camp veteran who has taught Albanian singing many times at the workshops; she’s profiled in the Fall/Winter 2002-03 issue.)

Merita, Jerry Kisslinger and Raif, Iroquois Springs, 2008. (photo: Margaret Loomis)

Merita says the students liked her voice and her singing, but some found the styles very difficult, even scary. Step by step, she says, she has worked to bring them more understanding and mastery of those styles. By the way, Merita’s brother Gëzim Halili taught clarinet at Balkan camp on two occasions.

“I see the people here looking for different cultures,” she says. “It’s good for me and everybody, and for this society. I give so much credit what they are doing. Everybody came from somewhere. It’s very good to bring a different culture and share food, history and beautiful lyrics and expressions.”

Raif was surprised by camp, too. “Living in Kosova,” he says, “we saw Americans as jazz, rock and roll, movies and MacDonald’s. To come here and see these Americans studying Balkan music, we thought, ‘these guys must be something very special or . . .' [he makes a gesture that indicates “funny in the head”].” He tried to find a reason why these Americans were doing this music; maybe they all had ancestors from that part of the world? Eventually he noticed a parallel with the way some of his music school friends back in Mitrovicë had been drawn to American music. They played jazz, soul music, Beatles and Rolling Stones—some of them, masterfully—even though they weren’t Americans.

Musical communion: Esma Redžepova dances to Merita’s singing at Ramblewood, 1998. (photo: Margaret Loomis)

“I understand that something is missing in people; that’s why they’re doing this,” he concluded. “Human beings are always looking for something that’s missing in their life—something spiritual. Music is spiritual; it’s soul.

“You know, you have things around you that you value but you don’t see from an outside point of view,” he said. “Later on, I realized Americans have a right to go crazy about Albanian and Balkan music. Because there is a lot in this music that people can find themselves within.”

What’s Up with the Keyboard Sheath?

Raif at Iroquois Springs, 2009 (photo: Margaret Loomis).