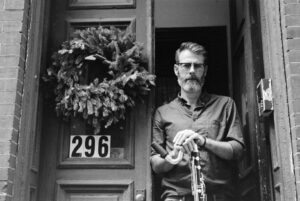

With Peter Stan, Live at Jalopy, 2017, photo by Nina Galicheva

Although Eva Salina represents the younger generation of American teachers at the EEFC workshops, she has been on staff off and on over the past 18 years. She has taught song survey courses, introductory singing, singing classes for kids, and Romani singing. As an American who “grew up at Balkan camp,” she is a professional performer and teacher whose work is steeped in Balkan music.

“When I was seven years old, someone gave me a cassette of some Yiddish songs,” Eva says. It was a recording of a 1970s-era LP recorded by members of Aman, the Los Angeles-based folk dance performing ensemble. Eva really connected with the voice of the singer, Pearl Rottenberg (later, Pearl Taylor). “These were not-so-well-known, beautiful Yiddish songs, and the lyrics were all transliterated in the liner notes,” she says. “I taught myself all of them.”

Her parents, Mark Primack and Janet Pollock, were not musicians but wanted to support their daughter’s enthusiasm for that style of music and started looking around their Santa Cruz community for someone who could give her lessons. They couldn’t find anyone singing Yiddish songs, but they did find a band, Medna Usta, performing Eastern European music in local cafes and clubs. Mark approached one of the members, Ruth Hunter, about the possibility of the 7-year-old Eva taking some lessons with her. Eva remembers Ruth walking up the hill to their house, accordion on her back.

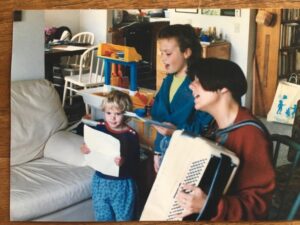

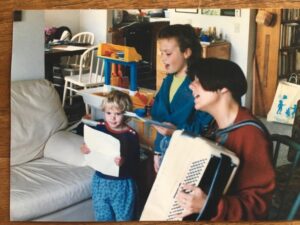

Luka and Eva taking a lesson with Ruth Hunter, Santa Cruz, 1992

“It was as if somebody had lit a pilot light inside me,” Eva said. “I was so moved and inspired by the music.” She continued to take lessons; Mark started taking accordion lessons with Ruth, and eventually Janet took singing lessons with her as well.

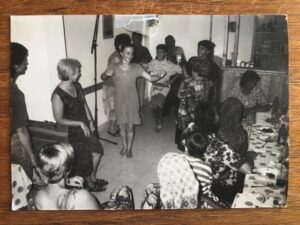

Around the same time, a neighbor, Susan Wagner, started hosting monthly gatherings called večerinkas, featuring folk dancing, live music, eating and socializing. Eva remembers Susan and another dancer/musician, Karen Guggenheim, welcoming her family into the gatherings, where they started to experience the music in a social context, integrated with food, dance, and community.

After a year of lessons, Eva’s teacher Ruth announced that she would be moving to Boston and suggested the family consider attending the EEFC workshops to continue learning the music. So in 1992, they went to three days of Balkan camp at Mendocino. Eva was 8 years old and her brother, Luka, was 2. The family loved the experience and began to attend camp every year for the full week.

Eva’s arrival at camp coincided with a shift in the teaching community from mostly American-born instructors to a gradual influx of teachers from Eastern Europe, especially Bulgaria, as a result of the fall of communism in the Balkans in 1989 and the subsequent opening of borders. Besides experiencing dancing and a variety of singing styles at camp, Eva began to study Bulgarian traditional singing, both at camp and with various Bulgarian teachers coming through town. She studied with Petrana Koutcheva, Svetla Angelova and Tatiana Sarbinska, with whom Eva took her first trip to Bulgaria, in 1996, at the age of 12.

Navigating music as a teenager

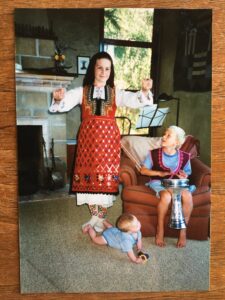

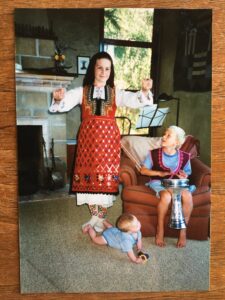

Eva, shortly after her return from Bulgaria, wearing an antique costume she purchased there; at home with her brother, Luka, and a small friend, 1996

“While I didn’t learn very much actual musical content on that trip,” Eva says, “I learned so much about the context and the history and the language and the land and the people that informed the music. That was critical for me in terms of not seeing Balkan music as something that existed once a year, in a little magical forest in northern California. It provided an opening into the complexity of the cultures surrounding the traditions, the history, the politics, religion, language, all of that.” Even at age 12, Eva found herself learning about the tensions that existed; the instability of the economy and the currency, and the active conflict going on in Bosnia and Herzegovina.

The following year, in 1997, Esma Redžepova and members of her ensemble, from Macedonia, came to teach at the workshops for the first time.

“The music Esma brought was electrifying and vibrant and expressive,” Eva says. “I felt a freedom in terms of how much room there was for each person to put their own emotions into the music. Not just freedom, but somehow an obligation to commit 100% to its soulfulness and spirit. That was a jumping-off point for me in terms of exploration, really wanting to feel that fullness and engagement all the time when I was playing music.”

Before that, Eva had been questioning her involvement with this music in the first place. It certainly wasn’t something she shared with her teenaged peers, and her ancestry didn’t link her to the traditions. She felt pressure to execute songs perfectly, rather than express herself through them. But learning about Balkan Romani music was the turning point.

“As much as technical precision or skill is prized within the different Romani musical genres, there’s also a tremendous value placed on a unique interpretation and a specific voice, an identifiable voice, whether it’s an instrument or a singer,” she says. “In working with Esma, I started to understand that that was not just a suggestion, but a requirement, and the more I explored that, the more I realized I could simultaneously study to improve my skill and also expand my own creativity. That it wasn’t just about, ‘do this for 25 years and maybe you’ll get it right,’ but that those two progressions could, and should, be happening simultaneously.”

When Eva was 14 or 15, she was asked to teach at Sweet’s Mill, a folk music camp northwest of Fresno, in the Sierra Foothills. Back in the ’70s, Sweet’s Mill had been the site of the earliest West Coast Balkan music and dance camps, but for years before and since then it has mainly been the home of general folk music camps with many traditions represented. Eva found it to be a looser context for learning and sharing, as opposed to what she perceived as a more academic approach at Balkan camp, which she also continued to attend. She discovered that the better she became as a teacher, the more confident and self-possessed she felt as a performer. She enjoyed helping people access their own power and expression.

She was invited to teach her first Balkan camp class in 2003, at Mendocino, a survey of Balkan singing. Although she felt “under a bit of a microscope” as one of not so many young people who have grown up in the community, her class and the ones in the years that followed were well received. In 2012, now that children occupied a larger space in the camp community, she suggested starting a children’s singing class at Mendocino—the class she wished she had had as a child.

Being a kid at camp

Dancing rŭčenica with a local boy, Bulgaria, 1996

A recurring cause of growing pains in the community throughout the history of Balkan camp has been the community’s stance on the presence of children at camp. (See the “Kids at Camp” story in our Fall 2007 issue.) Eva says that 20-plus years ago she felt like an unwelcome guest in some of the classes; her presence as a very young and quick learner could be disruptive for the adult students.

“It’s beautiful for me to see, especially now, the incredible amount of support, resources, time and energy surrounding the young people in our community, which is so different from how it was back then,” she says. “As destabilizing as it can feel to have a 14-year-old show up in your class who can grasp something very quickly, it’s actually the most hopeful thing that can happen to a community: to have young people who are just there blazing, building on the work of the generations before them. I think the best thing that we can do is support and trust the young people.”

Having felt “like an island out in the sea” when she was a teenager in the community, Eva is happy to see the many teenagers and young adults coming to today’s camps. In her most recent in-person class, at the 2019 Iroquois Springs camp, were numerous young people who had just been on the YAMMS (Young American Musicians to Macedonia and Serbia) trip.

“The kids who had been on that trip were so fired up, they wanted to talk about identity politics, cultural appropriation, gender dynamics—all these things that I feel we have to talk about now in order to work in these traditions responsibly,” Eva says. “It was so exciting to me to feel like I could both share my perspective and encourage them as they move forward on their journey.” In that same class at Iroquois Springs there was a 65-year age range of from the youngest person to the oldest in the class. Eva found it an exciting challenge to create a language of learning that could equally engage an 11-year-old and someone in their late 70s.

Mentors

When you become an adult in a community, Eva points out, you shift from everybody older than you being an authority, to being in a position where you can choose who your mentors are going to be. She feels grateful to have had a few close mentors in the community. The three that stand out the most for her are Ruth Hunter, Tzvetanka Varimezova and Ethel Raim.

We’ve already talked about Eva’s early work with Ruth Hunter. It was later, when Eva was 17, heading off to UCLA to study ethnomusicology, that she met Tzvetanka Varimezova, who arrived in Los Angeles at the same time. The Bulgarian singer was beginning a residency as an adjunct professor at UCLA. She has since become a favorite instructor at the EEFC workshops (see a profile about Tzvetanka in Kef Times, Spring 2013).

Eva Salina at Re:Orient Roma Festival, Stockholm, 2017

“[Tzvetanka] brought me back to Bulgarian music and helped me find my unique expression within the tradition that had been such a major part of my childhood,” Eva says. “She showed me how it was possible to be a complete and total musician and an extraordinarily generous teacher at the same time—to model that with grace and presence and great skill and diplomacy, and be confident enough in yourself and your abilities that you could empower everybody around you. She was, and still is, a huge influence on me, and a big inspiration.” Along the way, Eva completed a Bachelor of Arts in ethnomusicology from UCLA.

In 2007, when Eva moved to New York, through her friendship with Catherine Foster she came to know Ethel Raim, a singer well known to the EEFC community and a groundbreaking leader in folk arts research, preservation, documentation, programming, presenting and teaching, as well as the founder of the Pennywhistlers Balkan choral group in the 1960s.

“Ethel helped me to understand lineage and legacy,” Eva says. “Through knowing her I have come to identify the kind of cultural worker I want to be, and the lineage that I hope to be a part of in my work, particularly as a teacher. She has been tremendously generous and supportive with me on both a professional and personal level, and is an extraordinary musician, not to mention the work she has done to bring Balkan song, Yiddish song, and many other musics to new ears all around the world. Practically every time I teach, someone in their 60s or 70s who is in the workshop will come up to me and say, ‘45 years ago, I took a workshop with Ethel Raim, and it changed my life.’” [A note from your editor: Me, too.]

Performing

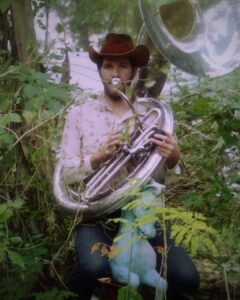

With Aurelia Shrenker, promotional shot for their duo, Æ, 2010

Eva has made guest appearances with many bands, toured internationally with Slavic Soul Party! and recorded with Édessa, Opa Cupa, and SSP!. She has produced four albums since 2009, available via streaming platforms and via Bandcamp and Apple Music (and you can always email her for hard copies: eva@evasalina.com).

In 2007, Eva started working with Aurelia Shrenker, a singer from Massachusetts she had connected with through Larry Gordon and Patty Cuyler of Village Harmony. They formed a duo called Æ, named after the printer’s symbol, pronounced “ash,” which provides an appealing typographical combination of their initials. They performed traditional music of the Balkans, Georgia, Corsica, and Appalachia; toured in several states; and produced a CD. Both women had studied multiple traditional singing genres; in this project they explored them together, playing between traditions.

“I grew to love the intimacy of a duo,” Eva says. “The Bulgarian women’s choir has a massive sound, but it’s also a created tradition. The brass band sound basically obliterates anything within a hundred yards of it sonically, and that’s great, it fills your body. But there’s almost a concept of chamber music in terms of how two people have to stay so present to each other. There’s no smoke and mirrors, there’s no artifice, there’s no fancy lighting, there’s nothing you can hide behind. Creating an intimate listening space around traditional music was something that I thought was important, and wasn’t happening enough.”

With similar intent, over the past 15 years, and more consistently in the last five, Eva has been touring together as a duo with accordionist Peter Stan. Peter was born in Australia but grew up in Queens; his family are Roma from Banat, the border region of Serbia and Romania. Together, they explore the listening side of Balkan Romani music.

“Everyone thinks that Serbian Romani music is only brass band music,” she says, “but actually, there’s all this listening music that gets mostly overlooked, outside of the Balkans. There are songs that were written equally for the accordion and the voice.

Eva and Peter Stan (promotional photo: Deborah Feingold Photography)

That was something we felt we could represent, just the two of us, and it would feel complete.” The two have appeared in many cities, including three European tours, and in two Library of Congress broadcasts. Information about their 2018 CD, Sudbina: A portrait of Vida Pavlović, can be found via Eva’s website.

Teaching: If you sit around waiting . . .

For the past six years Eva has directed a chorus at the Jalopy Theater and School of Music—a community chorus of about 35 people who sing traditional harmonies from the Balkans, Caucasus Georgia, Ukraine, Corsica and Sardinia, as well as from a variety of American folk singing traditions. She also sits on the organization’s nonprofit board. The chorus reunited this fall for their first outdoor season since March 2020, culminating the season with a performance at the Brooklyn Folk Festival in November, 2021.

At her 2019 Balkan camp class and in a series of online workshops over the past year, Eva has enjoyed working with students in a more solo- and performance-oriented way, helping singers access and develop more of their personal expression. She found the shift to online instruction actually aided this work, given that people were living and working from the comfort of their own homes and often felt more free to experiment without the pressure of an in-person group (and with the option of a mute button).

“If you sit around waiting for people to give you permission to be yourself within a tradition that you weren’t born into, you will be waiting a very long time,” she says. “I try to facilitate that [sense of permission] even with people who have never sung this music before. A lot of people have trouble accessing their own expression. Sometimes singing in a language that you don’t speak fluently can give you a little bit of a filter so you don’t feel quite so vulnerable, and so you can express or emote based on the melody. . . . You understand where the song comes from and what you’re singing about, but you also start to make this little secret story that’s just about you in the song, and what moves you within the song. I believe you can do that without compromising the language and the integrity and the history of the tradition.”

Eva also imports textiles and other items, visiting flea markets and local markets wherever she travels and bringing things home to share, and sets up booths at festivals where she’s also booked to perform. Since the onset of the pandemic, she has built up an online shop linked to her website to feature these imports, including jewelry, Turkish scarves and towels, and a proprietary skincare line (with a cult following) that she has created.

With Rosa, 2021

Eva and her partner, Ron Caswell, also a musician, have a two-year-old daughter, Rosa, and split their time between New York City and a small farm in Upstate New York. She’s eagerly looking forward to the opportunity to come teach at an in-person camp again, and introduce her daughter to the loving and family-friendly community of Balkan music and dance lovers.

“I’m very excited to raise a child in a healthy, intergenerational version of the EEFC community,” Eva says. “I think intergenerational communities are the richest resource we have right now because of how far we’ve gotten away from traditional ways of living. Being able to be in a dance line and have little kids running around, and for that to be okay, is so important. Children learn what they live, and I think the more inclusive we can be to them, the better off we’ll be in the long run.”

Location: I divide my time between Ashland, Ore., and Sebastopol, Calif.

Location: I divide my time between Ashland, Ore., and Sebastopol, Calif.