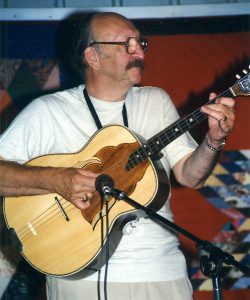

Paul Brown (photo: Sasha Pyle)

Paul D. Brown (the D is for Douglas) has been house bassist, a non-teaching staff role, at the EEFC workshops since 1996. He is known for his easygoing personal style and intense musical chops on both electric and acoustic bass. While consistently providing a reliable bass line in the many ensembles he plays with, he is also inventive and adventurous in his melodic playing. With an eye from the bandstand on almost every flavor of music presented at camp, he has a unique perspective on the scene.

When Paul Brown was a sophomore in high school, in Sunnyvale, Calif., he borrowed an electric bass from a friend and started trying to play what he heard on records he liked—progressive British rock bands like Yes, Genesis and Jethro Tull—music featuring a lot of melodic bass. He started taking lessons from a bass teacher at a local music store, who, he says, “set me on a path of studying music as opposed to just listening and playing it . . . learning modes and music theory.”

Paul’s family was not particularly focused on music. His two older sisters participated in school choirs and sang in the shower, but Paul is the only musician among the siblings. At age 18, he enrolled at UCLA, where he continued to play electric bass. By year three he had declared his major as music; he also started taking lessons on upright bass, although he was not to pursue that seriously until a couple of decades later. In his third year at UCLA, he learned about Berklee College of Music in Boston, a school based in contemporary music, which seemed a better fit than UCLA’s then classically based undergraduate program. At 20, Paul moved to Boston and earned his bachelor’s degree from Berklee.

“My degree was in professional music, so it was about playing bass and learning the role of the bass in a lot of different styles,” Paul says. “Berklee was a jazz school and I learned to play jazz there. I wouldn’t call myself a jazz player, even though I understand the idiom and can play it. But Berklee gave me a background in knowing what bass does in music and has done throughout the history of jazz and with specific types of rock and roll music.” His experience at Berklee opened his ears to many different styles of music, although the main kind of “world music” he learned about there was Latin music; he didn’t discover Balkan music until later.

After graduating, Paul moved back to the West Coast and eventually landed back in Los Angeles. Supplementing his musical life with temporary jobs usually centered on computers, he played with original rock bands, cover bands, and “at the height of income generation” an Irish folk/cover band that played three to four steady gigs per week. He toyed with the “music industry,” but never really latched on to it.

“I did peripheral stuff, kind of art music—cabaret rock, I think is what we called it back then—and contemporary and pop music,” he says. “That was where I met James Hoskins, who’s in this community. We were living in Los Angeles in the ’80s, playing in alternative bands, and crossed paths.”

Encountering Balkan music

With Polly Tapia Ferber (photo: Biz Hertzberg)

In the early ’90s, Paul met someone from the Los Angeles-based Balkan women’s chorus Nevenka, who gave him a cassette tape her group had just released.

“That was where I first heard the local Balkan music of California,” he says. “I’d heard the Bulgarian Women’s Choir, and may have heard Ivo Papasov, but this was somebody locally doing it.” Shortly after that he left L.A., moved to the Bay Area and met the community there, which started him on the path to Balkan music.

He attended a memorable event in spring 1994, probably at La Peña Cultural Center in Berkeley: a concert by Savina Women’s Folk Choir followed by a dance party. The tamburica band Zapadne Lole was playing: Mark Forry, Bill Cope, Joe Finn, Suzanne Leonora and Allan Cline.

“I saw them play and I saw the people dancing and I said, okay, this is different . . . and very interesting,” Paul says.

At that concert, he picked up a copy of Bill Cope’s Balkantunes newsletter and learned about Balkan camp. That summer, he drove up to Mendocino Balkan camp for a day and saw his friends from Zapadne Lole—and many others—playing music. Everybody wanted to know who the newcomer was.

“It was a great night,” he says. “I left the next day for a gig in Los Angeles and realized I wanted to go back to that.” A year later, he returned to the Mendocino Woodlands for the weeklong workshop, spending much of his time understudying with then-EEFC house bassist Allan Cline, who invited him to sit in on a few sets.

Paul attending a Greek ensemble class at the 2013 Mendocino workshop (photo: Bill Lanphier)

Allan was about to go to Turkey with his wife, Nancy Klein, an accomplished folk dancer and doumbek player. He was going there to study oud; they were to be gone for at least six months. Zapadne Lole needed a replacement bass player while Allan was out of town. At the request of band leader Mark Forry, Paul agreed to sit in. At this time Paul was living in Castro Valley, Calif., and continuing to play many other kinds of music.

While Allan and Nancy were driving in Greece that summer, a car accident killed Allan and injured Nancy severely. Besides being a personal tragedy for their families and friends, this was a blow to the EEFC organization and community. EEFC asked Paul to replace Allan as house bassist at both workshops—Mendocino and Ramblewood—the following year. He has been house bassist at the Mendocino workshop every year since, and at East Coast camp in many of those years.

(photo: Margaret Loomis)

The way the rhythms groove

What was it about Balkan music that attracted him? “For me, being a bass player, it was the rhythms,” Paul says. ”The odd rhythms and the way they groove so easily. I also liked the harmonies and dissonances, especially vocally. The vocal music was some of the first music I heard that I loved—especially styles like the Macedonian diaphonics with really close second intervals—that just blows me away. And the Bulgarian arranged Kutev-style material.

“And then the improvisational music of the old styles in Ottoman music has fascinated me,” he adds. He had the opportunity to explore those styles with Orkestra Keyif, an ensemble grounded in Ottoman Turkish and Balkan music, made up of musicians scattered across North America, including, originally, Haig Manoukian. Current and sometime members include Brenna MacCrimmon, Beth Bahia Cohen, Lefteris Bournias, Paul Brown, Polly Tapia Ferber, Adam Good and Phaedon Sinis.

“That opened up another world of music for me in the New York scene,” Paul says, “with Haig and Souren [Baronian] and the band Taksim. That band married a lot of my musical paths and passions—wonderful music, including original compositions, with a lot of improvisation and unison lines.” Paul played with Taksim from 2003 to 2009, including at the Montreal Jazz Festval in 2004, and continues to occasionally sit in with the band.

With Christi Profitt (photo: Biz Hertzberg)

Being the bassist

Being house bassist is, Paul says, “the best job at camp. I don’t teach a class, but as house bassist I play with the faculty and staff and a lot of the campers, many of the pick-up bands, because it’s fun and some of that music is amazing. The job is just to be available to play for the evening dance parties and for some of the classes, and also in the kafana when it’s needed.” Many of the faculty members ask him to sit in with their ensembles.

“Some of the music needs it, like the tamburica music, and some of the Greek island music wouldn’t need it. So . . . role-appropriate. Why Pontic Firebird works is anybody’s guess.” (Pontic Firebird is another band Paul plays in. It’s a bi-coastal ensemble playing Western Pontic dance music: Greek music from Turkey’s Black Sea coast. Paul plays acoustic bass; the other players are Beth Bahia Cohen, violin; Adam Good, oud; and Jerry Kisslinger, daouli.)

Paul’s main Balkan music project is with the Bay Area-based dance band Édessa (George Chittenden, Lise Liepman, Ari Langer, Sean Tergis and occasional guest artists). Added as “the bottom we didn’t know we needed” in 2001, Paul travels with them to many dance events around the country, such as: Ahmet Lüleci’s World Camp in New York; Razzmatazz, a weekend camp held in early June at Mendocino Woodlands Camp 1; and to an annual glendi (Greek dance party) in Santa Rosa. The group has been hired to play for many dance camps over the years, including in Mexico, and several times a year plays dance parties at Ashkenaz Community Center in Berkeley, including many New Year’s Eves.

Paul’s current band at home in Santa Fe is Evet. The word is Turkish for “yes.” Consisting of Paul, Polly Tapia Ferber, Nicholas Kunz, Willa Roberts, Char Rothschild and Melinda Russial, the band plays pan-Balkan and some Middle Eastern music. “Everybody sings in this band and everybody plays multiple instruments, although only Char plays them simultaneously,” he says. “It’s very exciting.”

Paul also performs several times per year with Boulder-based Sherefe, a band that plays Greek, Turkish and Middle Eastern music; Paul’s longtime friend James Hoskins is a member, along with Jesse Manno, Brett Bowen, Julie Lancaster, Dexter Payne and, sometimes, Beth Quist. When in New York (or at Balkan camp or Golden Festival) he performs with Kavala Brass Band (members and alumni of Zlatne Uste Brass Band), which focuses on Greek Macedonian Aegean repertoire, and Pontic Firebird.

An enviable rhythm section: Paul Brown, Jerry Kisslinger and Matt Moran at the 2015 Iroquois Springs workshop (photo: Margaret Loomis)

Within the last few years Paul earned an associate’s degree in nursing from Santa Fe Community College. He worked as a nurse briefly but is not doing so now; he says he really enjoys nursing work and will probably go back to it.

As a professional musician, Paul is not limited to Eastern European or Middle Eastern music. From his home base in Santa Fe, he plays a weekly upright bass gig with a pianist playing original Latin jazz improvisational music, and sometimes plays locally with other jazz artists. He often plays with the duo Round Mountain (Char and Robbie Rothschild, a “two-man singing folk orchestra”) when they are in town. From time to time he has taught, including at the College of Santa Fe, and has had a few private students, but he depends more on performance than on teaching.

Besides the bass Paul also plays oud, some piano and sousaphone. He is interested in exploring a specific style of laouto playing, inspired by Boston-based Vasilis Kostas’s work with master clarinetist Petroloukas Halkias (see link and link).

“But the oud is challenging enough,” he says. “I really like it and I have a beautiful instrument that I got from Haig, after Haig passed away [see Kef Times, spring 2014, that I love playing. But the bass has always been my instrument. It’s just the thing I’ve always liked doing.” Paul originally studied oud with Haig Manoukian and Necati Çelik in 1995 and in the last year has taken a workshop with Yordal Tokcan to improve his skills.

(photo: Bill Lanphier)

Tips for bass players

How do you learn to play bass for such a variety of genres? Besides listening to a lot of source recordings, Paul says it’s a matter of understanding the role of bass in music.

“Bass is similar in different genres,” he says. “Tone might be different, or the attack, but the role is similar: it’s a rhythm instrument but it’s also a melodic instrument. You have to bridge that gap, making sure that you’re keeping the rhythm—especially since a lot of this music is dance music—propelling it in a good rhythm for dancers and make it interesting musically, because it’s a musical instrument, while not stepping over the other instruments.

“Have fun with it,” he says. “That’s always a good thing if you’re playing music. It’s an energetic thing, too. If you’re having fun, that energy spreads to the people listening and watching.”